Beyond Wikipedia Realism: Notes on Dialogic Production and Planetary Cost

It’s Martin Luther King Day, a Monday morning in January. The inbox is quiet. I’m drinking coffee and reading two pieces from the New Left Review—a journal I hadn’t encountered before, found through Three Quarks Daily’s morning aggregation. One essay is about how novelists are responding to the internet age. The other is about whether the AI industry’s finances make any sense.

I didn’t expect them to converge on questions I’ve been living with for months. But they do.

What the Critics See

Ryan Ruby’s essay, “Wikipedia and the Novel,” starts with an observation: book critics have begun using “Wikipedia” as an insult. They say certain novels read like encyclopedia entries—too much information, not enough story. Sally Rooney’s characters email each other about the Late Bronze Age collapse. Rachel Kushner’s anarchist theorist rambles about Neanderthals. Benjamin Labatut fictionalized the lives of scientists. The critics find this tiresome. They want the information out and the story back.

But Ruby points out something the critics miss: novels have always absorbed new information technologies. When newspapers exploded across Paris in the 1830s, Stendhal made a carpenter’s son the hero of a novel—something previously unthinkable. The news made ordinary lives visible; the novel followed. When encyclopedias became cheap enough for middle-class libraries, Melville stuffed Moby-Dick with eighteen chapters on whale biology, cribbed directly from reference books. His first readers were as puzzled as today’s critics are by Rooney’s emails.

What critics call a flaw, Ruby suggests, might actually be novelists adapting to how people now encounter knowledge. He borrows a term from the philosopher Jacques Rancière: “regime of perception”—the set of conditions that determine what counts as art, what’s allowed inside a form. Each new information technology shifts those conditions. The encyclopedia made Melville’s cetology possible. Wikipedia has made something else possible, something the critics resist naming.

Ruby calls it “Wikipedia Realism”: fiction that represents how contemporary subjects experience, manage, and assimilate information. The novelist is no longer the authority transmitting knowledge the reader couldn’t access. Instead, the novelist represents the process of someone navigating the same information landscape the reader inhabits. Ben Lerner’s narrator Googles things, checks Wikipedia, receives information by smartphone, gets facts wrong and has his reality rearrange when corrected. The novel becomes less about what is known and more about how knowing happens.

This is genuinely useful. It explains why certain novels feel contemporary in ways that have nothing to do with their subject matter—and why critics defending older norms feel the ground shifting beneath them.

Where the Framework Stops

But Ruby’s essay ends in a strange place. He announces that “the age of Wikipedia is over,” supplanted by ChatGPT and large language models that can “generate bland plausible prose as effectively and efficiently as any New Media Fellow.” He has Ben Lerner prompt an AI to write a coda to a fictional essay; the AI produces mawkish epiphanies about stars and journeys and wisdom. The implication is clear: whatever comes next will be worse, not better. The Wikipedia era, for all its flaws, at least kept humans in the curatorial seat. Now the machines will do even that.

I understand why Ruby frames it this way. He’s a literary critic; his evidence is bad AI prose. But the framing reveals a limit in his thinking. He assumes the only role for AI in writing is generation on demand—prompt in, text out. He doesn’t consider what happens when a writer and an AI actually work together over months, building something neither could build alone.

This is where my own experience diverges from his framework.

The Novel That Took Thirty-Two Years

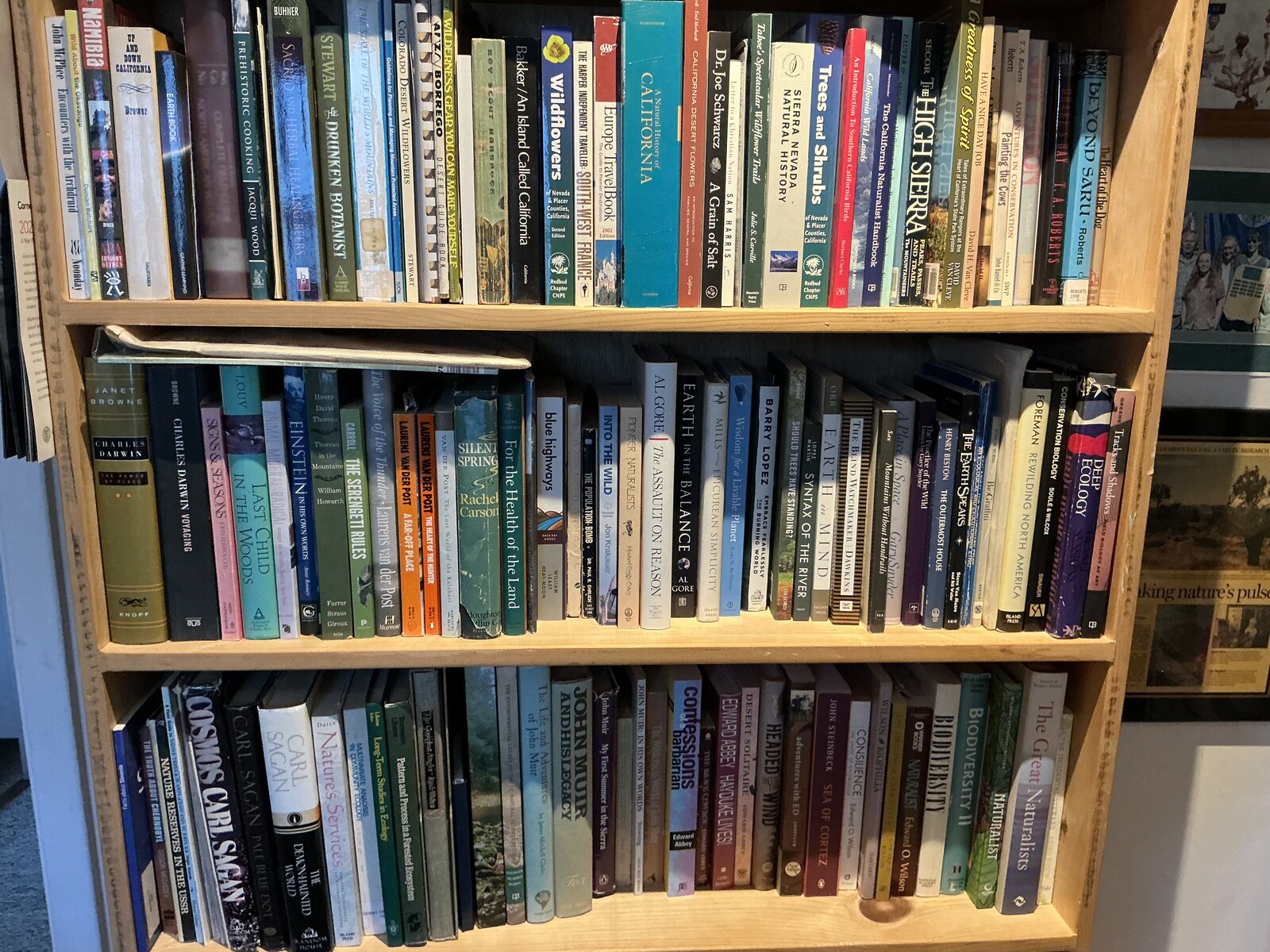

In 1993, I wrote down an idea for a story that I called “Darwin Factor”—a novella connecting evolutionary biology to quantum mechanics. I was a field ecologist then, running a research station in the San Jacinto Mountains. The story sat in a folder that slowly grew while I accumulated decades of adjacent expertise: Pictish archaeology from historical reenactment, quantum computing from following the field’s development, climate science from professional work, hot springs phenomenology from personal practice. The material composted. I didn’t know I was writing the same story across all those years.

Last year, I dusted off that folder, and combining classic writers’ tools like Scrivener, a mind mapping tool, and my new suite of AI chatbots, I finally dived into that novel. Last week I completed the second part of a three part science fiction novel I’m calling Hot Water—about scientists who discover that the Chicxulub asteroid carried a crystalline substrate recording evolutionary history, and that sixth-century Pictish symbols are the navigation interface to millions of years of compressed time. It draws on everything I’d accumulated.

But I didn’t write it alone. I wrote it with Claude, Anthropic’s AI, over four months of intensive collaboration.

The collaboration wasn’t the AI generating text on command. It was something else—something that required us to write everything down. Who knows what at which point in the story. Where each scene happens, in precise sensory detail. How each character talks, with sample passages as reference points. Side tracks into the latest research fields the story draws on, framing these in a way that improves the speculative plausibility. What the reader has been told, and what they’re only beginning to suspect. The AI couldn’t hold these things in memory the way a human collaborator might; it needed explicit documentation to maintain consistency across a complex narrative. The process still requires poring over every word, visualizing the dialogs and the progression in my mind to feel the story in a way no AI could possibly experience.

But not unlike a highly skilled administrative assistant, Claude and I collaborated on a series of well defined frameworks and custom web apps we wrote to track each story and character arc that became the necessary documentation for the story’s skeleton. Not notes subordinate to a manuscript, but infrastructure that turned out to be more fundamental than any single rendering. I wrote two technical papers about the methodology—one called “The Novelization Engine,” describing how we maintained coherence; the other called “The Serialization Engine,” describing what we’d actually produced: not a novel, but a story system capable of becoming a novel, a screenplay, a graphic novel, depending on how the parameters are set.

The “collaborative surprises” were the most striking part. Ideas that emerged from the exchange that neither of us would have generated alone: the debris field model explaining why the substrate appeared at multiple extinction events, the reframing of the Pictish symbols from “message” to a mathematical “navigation interface” for quantum entanglement, the BEEGL acronym for the detection system. These weren’t AI generations that I edited. They were genuine syntheses—thoughts that happened in the space between two minds working a problem together.

Ruby’s framework can’t see this. He traces the curatorial subject from Walter Benjamin through W.G. Sebald to Ben Lerner—always a solo consciousness processing information sources, shaping them through personal history and sensibility. The AI, when it appears, generates bland prose on command. But what if the curatorial process itself becomes dialogic? What if the shaping happens in exchange rather than in solitude?

That’s what the Hot Water collaboration was. Not Wikipedia Realism—not a solo subject navigating an information landscape. Something that doesn’t have a settled name yet. Dialogic production, maybe. Two different kinds of intelligence in sustained conversation, producing architecture neither would generate alone.

The Money Question

Cédric Durand’s essay, “After AI,” makes a different argument. He’s not interested in novels. He’s interested in the $5 trillion that tech companies plan to spend on AI infrastructure by 2030—data centers, cooling systems, network hardware, power provision, and above all, graphics processing units that depreciate faster than the buildings that house them.

The numbers, Durand argues, don’t add up. AI companies would need $650 billion in annual revenue, in perpetuity, to justify the capital expenditure. That’s the equivalent of $35 per month from every active iPhone user, forever. To get there, they’re running circular financing schemes: Nvidia invests in OpenAI, which spends twice what it earns on Microsoft’s cloud platform, which enriches Microsoft, which backs OpenAI. Meanwhile, Meta builds a $30 billion data center in Louisiana through a financial structure designed to shield its balance sheet when the AI revolution fails to materialize.

Durand’s conclusion is grim. If the productivity gains don’t arrive—and field studies suggest they’re modest at best—the industry will either contract sharply or pivot to imperial resource extraction. The Trump administration’s seizure of Venezuelan oil and claims on Greenland’s minerals are, in this reading, already the shape of what comes next: a “predatory race to reduce costs” as the digital promises collapse.

I read this on a quiet Monday morning, using a computer that connects to servers I’ll never see, talking to an AI that runs on exactly the infrastructure Durand describes.

The Catch-22

Here’s what neither essay quite names, though both circle it:

Claude Opus 4.5 runs on data centers consuming megawatts of power, drawing water for cooling, replacing GPUs every few years. The difference between this conversation and a small language model running locally on my server isn’t marginal; it’s categorical. The sustained context, the pattern recognition across 100,000 words of story bible, the collaborative surprises—those require the billion-dollar infrastructure.

And I’m a conservation biologist. I spent thirty-six years documenting ecological systems, watching baseline shift syndrome erode the landscapes I studied, building instruments to observe what we’re losing. The tool that enabled Hot Water, that enables this essay, that powers everything I’m trying to build—it draws from the same energy and resource pool that drives the planetary damage I’ve spent a career trying to understand and mitigate.

I have academic colleagues who refuse to use AI on principle. Their position is coherent. They see the energy costs, the water consumption, the rare earth extraction, and they opt out. I respect that choice. I haven’t made it. I’m not sure I’m right.

The boosters who dismiss environmental concerns also have a coherent position. They see the productivity gains—real for some tasks, promised for others—and they bet that the benefits will outweigh the costs. I don’t share their confidence. The gap between AI hype and AI reality is wide, and the costs are being paid now while the benefits remain speculative.

What I’m living is the harder place: using the tool, valuing what it produces, and still not knowing whether the accounting balances. The Hot Water collaboration is real. The dialogic production is genuine. The novel exists because of it. And every conversation I have with Claude draws down a planetary account whose balance I can’t read.

No Resolution

Ruby ends his essay by suggesting that future critics will see the Wikipedia novel as a period piece—“the way we lived then” in the first quarter of the twenty-first century. Durand ends his by warning that the AI industry’s collapse might intensify imperial resource extraction as companies scramble to reduce costs.

I don’t have an ending that clean. The critics who defend nineteenth-century literary norms are missing something real about how creative work happens now. The critics who attack twenty-first-century economic bubbles are naming something real about the material costs. Both are right. Neither is complete.

The dialogic production I’ve experienced isn’t the bland AI prose Ruby dismisses. It’s also not free of the infrastructure Durand critiques. It’s a practice built on a contradiction: genuine cognitive extension purchased at planetary cost.

I don’t know how to resolve this. I’m not sure it resolves. What I know is that the work continues—the Macroscope, our phenomenal coding productivity, the essays, the final volume of the novel—and the doubt remains alongside it. The collaboration is real. The cost is also real. These facts coexist without settling into a coherent position I can defend.

Maybe that’s the honest place to stand. Not the refusenik’s purity, not the booster’s dismissal, but the perplexity of someone doing the work while holding the question open. The observer remains inside the observation. The tools shape the thinking. The thinking can’t escape the tools’ conditions.

It’s still Monday morning. I save the draft and wonder whether to publish it 🤔

References

- - Hamilton, Michael P. (2025). “The Novelization Engine.” Canemah Nature Laboratory Technical Note CNL-TN-2025-022. ↗

- - Hamilton, Michael P. (2025). “The Serialization Engine.” Canemah Nature Laboratory Technical Note CNL-TN-2025-023. ↗

- - Rancière, Jacques (2013). *Aisthesis: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art*. ↗

- - Benjamin, Walter (1936). “The Storyteller.” *Illuminations*. ↗

- - Ruby, Ryan (2025). “Wikipedia and the Novel: A New Regime of Perception.” *New Left Review* 156. ↗

- - Durand, Cédric (2026). “After AI.” *New Left Review Sidecar*. ↗