From Powerless to Purposeful: A Morning with Mills and Memory

This morning began as so many do—coffee in hand, the house still quiet, settling into my reading chair for what I call my 'Coffee with Claude' sessions. These early hours are sacred time for synthesis and reflection, a practice I've maintained since retirement. Today I encountered C. Wright Mills' 1945 essay 'The Powerless People: The Social Role of the Intellectual,' published in the Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors during the final months of World War II.

Reading Mills eighty years after he wrote these words, I experienced something rare and unsettling: the shock of recognition. Not the comfortable familiarity of confirming what one already knows, but the disorienting vertigo of seeing one's own professional life dissected by someone who died before I was born. Mills was diagnosing trends he saw emerging in 1945; I lived through their full realization across thirty-six years in academic field ecology.

The Central Paradox

Mills identifies what he calls the fundamental crisis of the modern intellectual: 'We continue to know more and more about modern society, but we find the centers of political initiative less and less accessible.' The cruel paradox he articulates with surgical precision is that 'the more his knowledge of affairs grows, the less effective the impact of his thinking seems to become.' Knowledge, rather than conferring power, generates its opposite—a profound sense of helplessness.

I felt Mills speaking directly to my experience. But the recognition wasn't simple. My career trajectory initially seems to contradict his thesis—I moved from independent field naturalist to positions of increasing institutional influence, securing major NSF funding, helping shape national ecological infrastructure through NEON, co-directing the forty-million-dollar Center for Embedded Networked Sensing. By conventional metrics, I was successful at translating knowledge into institutional power.

Yet Mills would recognize immediately what that success cost.

The Boots-on-the-Ground Years

I began my career as what Mills celebrates: the independent intellectual craftsman. As Director of the James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve at UC Riverside, and later at Blue Oak Ranch Reserve at UC Berkeley, I lived at my field stations. Faculty and graduate students would arrive for their research projects, often uncertain about where to establish study sites or how to navigate the practical constraints of remote field work. My role was consultative and collaborative—I knew where the springs were, which slopes harbored the most diverse plant communities, when the phenological windows opened, what the realities of equipment deployment in wilderness conditions actually meant.

This was intellectually gratifying work in exactly the sense Mills describes. I brought deep, place-based knowledge to bear on helping others formulate meaningful research questions. The 'craftsmanship central to all intellectual and artistic gratification' that Mills says is being thwarted for modern intellectuals—I experienced that directly, daily. When a graduate student's research design collided with ecological reality, I could walk them through alternatives grounded in intimate knowledge of the system. When equipment failed in remote deployment, I was there to troubleshoot. This was science as embodied practice, rooted in direct observation and accumulated wisdom.

Living at the reserve meant the boundaries between work and life dissolved productively. I could walk out my door into thousands of hectares of protected ecosystems. Morning observations before breakfast. Late afternoon bird surveys. The continuous awareness of seasonal rhythms, of what was flowering, what wildlife was moving through, how drought or rainfall was shaping community dynamics. This was Mills' ideal: the intellectual whose thinking remained connected to direct experience, whose knowledge was verified through sustained engagement rather than mediated through institutional structures.

The Administrative Ascent

Then came the larger interdisciplinary collaborations. The NSF Center for Embedded Networked Sensing. The NEON Design Consortium, where I co-chaired the Sensors and Networking group. Major infrastructure grants requiring multi-institutional coordination. Suddenly I was operating at scales that amplified my influence—shaping national sensor network architecture, guiding distributed environmental monitoring strategies, helping establish standards for ecological cyberinfrastructure.

This is where Mills' analysis becomes uncomfortably precise. He writes: 'The means of effective communication are being expropriated from the intellectual worker. The material basis of his initiative and intellectual freedom is no longer in his hands.' As I moved into these larger coordinating roles, I gained institutional influence but lost direct connection to fieldwork. Instead of walking outside to check on sensor deployments, I was chairing committees about sensor standards. Instead of troubleshooting equipment failures myself, I was reviewing progress reports from multiple field sites.

The irony is that this trajectory felt necessary for the work I cared about. Mills identifies the trap precisely: 'If the small business man escapes being turned into an employee of a chain or a corporation, one has only to listen to his pleas for help before small business committees to realize his dependence.' Scale up or become irrelevant—that's the message modern science delivers. Individual field stations studying local phenomena can't address questions about continental-scale climate patterns, phenological shifts, or ecosystem responses to global change. To pursue those questions, you need coordinated networks, standardized protocols, integrated databases, sustained funding.

As a field station director living on site, I maintained considerable independence. Students and faculty came to me; I didn't depend on distant facilities or resources I couldn't access. But as research questions scaled up—distributed sensor networks across landscapes, multi-year phenological monitoring, integration of data from multiple sites—the individual investigator model became inadequate. Not wrong, but insufficient. The questions I most wanted to pursue required exactly the kind of collective infrastructure that brought administrative burden.

Mills writes of intellectuals who 'know more than they say and they are powerless and afraid.' The fear in academic science is more nuanced than overt censorship. It's the internalized calculation about which projects are fundable, which questions fit current paradigms, which approaches align with foundation priorities. Grant writing becomes an exercise in translation—taking the research you want to do and framing it in terms that satisfy multiple stakeholders. Over time, this shapes not just how you present work but which questions seem worth pursuing.

Retirement and Reclamation

Mills warns about the trap of pure introspection: 'If ethical and political problems are defined solely in terms of the way they affect the individual, he may enrich his experience, expand his sensitivities, and perhaps adjust to his own suffering. But he will not solve the problems he is up against.' This cuts to the heart of what retirement threatened.

When I retired from Blue Oak Ranch Reserve in 2016, I experienced what many academics face: the abrupt transition from institutional relevance to invisibility. The phone stops ringing. The invitations to review panels cease. You're the same person with the same knowledge, but suddenly lacking the positional authority that made that knowledge matter to institutions. The temptation Mills identifies becomes powerful—to retreat into private cultivation, enriching personal experience while withdrawing from collective engagement.

But my situation was more complex than simple exile. I moved to Oregon City for family—my daughter nearby, the support network I need as I age, proximity to those I love. This wasn't compromise but realism. Retirement released me from the administrative burden that had increasingly separated me from fieldwork itself. I didn't mourn the loss of committee meetings and grant management. I mourned the loss of institutional infrastructure—students, faculty collaborators, research budgets, shared endeavors. But I was relieved to reclaim direct engagement with observation and discovery.

The Macroscope as Response

The Macroscope project I've been developing represents my response to Mills' critique. It refuses the purely introspective retreat he warns against while acknowledging the constraints he identifies. Yes, it's personal—my own health metrics, my backyard observations, my home laboratory. But I'm architecting it as paradigm, as distributed sensing philosophy, as potentially replicable framework.

Mills argues that 'knowledge that is not communicated has a way of turning the mind sour.' The Macroscope resists this by maintaining scholarly engagement even without institutional affiliation. My morning sessions synthesize literature, work through ideas, connect observations to larger patterns. The documentation and architecture I'm developing could serve others pursuing similar approaches. I'm not simply building private infrastructure for personal use—I'm working to demonstrate alternative models for sustained, systematic observation outside institutional frameworks.

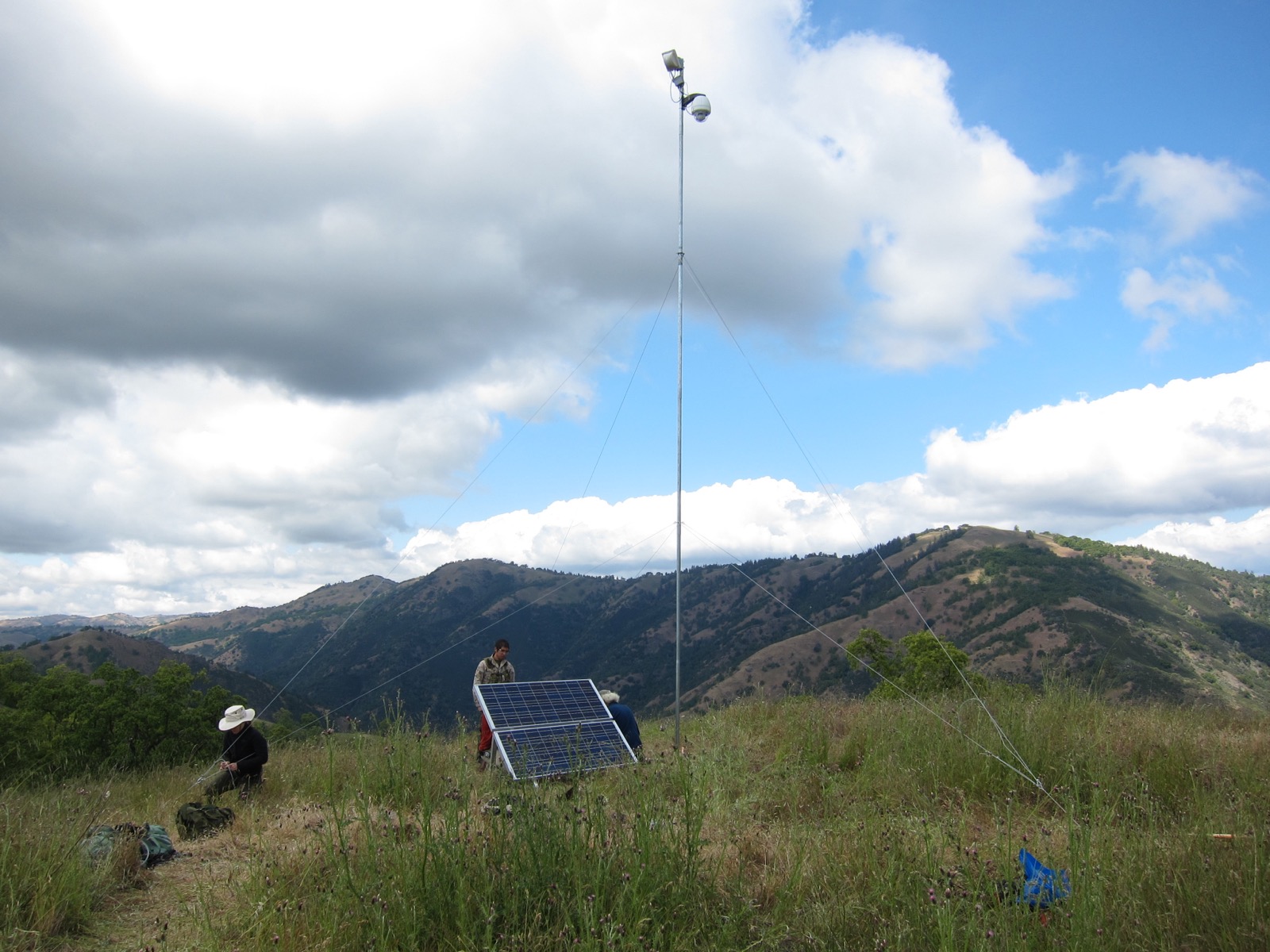

The tools I deploy reflect this hybrid approach. Low-cost IoT devices—weather stations, garden sensors, webcams, air quality monitors—provide continuous streams of environmental data. DIY Raspberry Pi components fill development gaps that twenty years ago would have required a full-time postdoctoral engineer and significant budget for custom micro-fabrication. The contrast with my earlier work is almost absurd: after decades of deploying miles of long-haul wireless networks at field stations to achieve maybe 100 Mbps at costs of tens of thousands of dollars, I now plug into reliable 1Gb fiber optic service and serve my own web applications from low-powered servers on my desk.

The enabling technology extends beyond hardware. Armed with LLM-assisted coding tools I could only dream about a decade ago, I'm building applications at levels of sophistication that computer science and data science students pursue entire degrees to master. These are affordable, accessible technologies that don't require institutional budgets or grant cycles. The DIY ethos that characterized early CENS work with wireless sensor motes persists, now liberated from institutional procurement processes and committee approvals.

Mills would push harder, asking whether this constitutes genuine engagement with collective problems or sophisticated adjustment to powerlessness. It's a fair question. I can't shape NEON's continental-scale infrastructure anymore. I can't direct graduate student cohorts or coordinate multi-institutional field campaigns. But I can demonstrate that systematic observation, thoughtful integration of sensing technologies, and sustained attention to multi-scale patterns remain possible—and meaningful—outside institutional structures.

The Explorer-Scientist Synthesis

Through all these transitions, I've maintained what I think of as my core identity: the explorer-scientist hybrid. This isn't romantic naturalism divorced from measurement, nor reductionist quantification divorced from wonder. It's the synergy between them. The explorer's curiosity about what's happening drives the scientist's systematic observation, which in turn reveals new phenomena to explore.

Living at field stations gave me something Mills says is essential for intellectual integrity: maintaining 'the material basis of initiative and intellectual freedom' even while institutionally embedded. My home was my laboratory, my study site, my refuge from administrative machinery. Even now, though my backyard in Oregon City isn't thousands of hectares of protected wilderness, it serves as observation site, experimental platform, and a testing ground for sensing technologies.

Mills writes that 'the basis of our integrity can be gained or renewed only by activity, including communication, in which we may give ourselves with a minimum of repression.' The administrative work I found horrendous required maximum repression of my actual interests. Not because it was meaningless, but because it prevented me from doing what I was trained for and what I love—direct engagement with ecological systems, helping others learn to observe carefully, developing tools that extend our capacity to notice patterns.

Forward into the Remaining Decades

Mills ends his essay bleakly: 'Our impersonal defeat has spun a tragic plot and many are betrayed by what is false within them.' The defeat he describes isn't at the hands of a clear enemy but arises from structural conditions—the centralization of decision-making, the expropriation of communication channels, the transformation of intellectual work into institutional employment.

I refuse his tragic ending. Not through naive optimism, but through recognition that the structural constraints he identified don't preclude meaningful work—they reshape its forms. I can't operate at the institutional scales I once did, but I've reclaimed direct observational practice. I can't secure major NSF funding anymore, but I can deploy affordable sensing technologies on my own timeline and terms. I can't direct cohorts of graduate students, but I can maintain scholarly dialogue through other channels.

The remaining decades of my life are not exile or retreat. They're an opportunity to demonstrate alternative approaches to sustained systematic observation, to integrate personal health monitoring with environmental sensing and cognitive tracking, to show that the Macroscope paradigm I've been developing since 1986 remains viable and valuable outside institutional structures. The four domains—EARTH, LIFE, HOME, SELF—continue to organize my attention and my tools.

Mills was right about the structural conditions that make intellectual work difficult in modern bureaucratized societies. But he may have underestimated the resilience of the explorer-scientist hybrid, the person who maintains curiosity-driven observation regardless of institutional context. Living near family in Oregon City, collaborating when opportunities arise, traveling monthly for sustained immersion in the protected natural areas of Washington and Oregon, developing Macroscope infrastructure in my home laboratory—this isn't compromise or defeat. It's adaptation, in the most biological sense: adjusting to constraints while maintaining essential functions.

This morning's coffee with Mills has crystallized something I've felt but couldn't articulate: the trajectory from field naturalist to big science administrator to independent observer isn't failure to maintain institutional relevance. It's a career-long experiment in finding where meaningful intellectual work remains possible. The newly-minted Ph.D. beginning as Director of James Reserve in 1982, the CENS co-PI coordinating distributed sensor networks in 2002, the retired director developing personal sensing networks in 2025—these aren't different people but different positions from which the same person pursues the same fundamental questions.

Mills wrote during World War II about intellectuals suffering "the tremors of men who face overwhelming defeat." I write from my home office in Oregon City, surrounded by servers and sensors, planning my monthly trip north to Washington's natural areas, developing tools for what I call the digital naturalist. The institutional phase of my career—with all its genuine accomplishments and genuine frustrations—gave me tools, connections, and perspectives I still draw on. But I'm grateful to be free of its administrative burden, grateful to have reclaimed direct engagement with observation and discovery.

Most of all, I'm grateful for the decades ahead, whatever they hold, because they offer continued opportunity to observe, to understand, to develop tools that extend human capacity to notice what's happening in the intricate, beautiful, threatened systems we're part of. The Macroscope paradigm I began articulating in 1986 remains my organizing framework. The explorer-scientist hybrid identity persists. The curiosity that drew me to field biology continues undiminished.

This morning's coffee was excellent. Mills was prescient. And the work continues.

References

- - Mills, C.W. (1945). "The Powerless People: The Social Rôle of the Intellectual." *Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors (1915-1955)*, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 231-243. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40221218 ↗