Cognitive Poetry: On Dreams, Clocks, and the Phenology of Ideas

I woke this morning with a question already forming: what are ideas?

Not the philosophical abstraction, but the operational puzzle. Where do they come from? How would you build a machine that generates them? And trailing the question, a mechanism—fully formed, waiting at the threshold of consciousness. An idea about ideas, arrived from the dream state before I could catch it forming.

The honest answer is that I cannot fully explain where it came from. I can trace conditions. Fifty years of naturalist practice. Decades of reading compressed into what I can only call prepared recognition. A research paper about textile computing that had arrived the day before and resonated with old work on walkabout data loggers. The dream continuing to process while consciousness was offline.

But the synthesis itself? That configuration didn't exist anywhere before it existed in my mind this morning.

This is the puzzle at the center.

The mechanism that surfaced was this: build an idea clock. An AI agent that periodically samples random patterns from Wikipedia—articles and images, chaotically various, Mongolian throat singing adjacent to carburetor design adjacent to a fourteenth-century Italian bishop. The agent timestamps the sets, pauses, randomly starts again, accumulates. Then it sleeps. During sleep, temporal and spatial coherence loosen. Things that were sequential become simultaneous. Things that were distant become adjacent. The dream isn't random—it's constrained noise, bounded by what has been sampled.

When you nudge the clock, it wakes. And in the hypnopompic transition, before full coherence clamps down, it speaks from the buffer. Three outputs: a limerick forcing comedic compression, a haiku forcing stillness and juxtaposition, a what-if reaching for propositional novelty.

The clock doesn't solve problems. It composes juxtapositions and waits for recognition.

I have been thinking about clocks for a long time.

During my decade as director of Blue Oak Ranch Reserve, we maintained a blanket policy: any academic discipline with a legitimate class or project integrating landscape and nature could use the station, provided impacts remained minimal. Scientists and artists, writers and photographers, naturalists and philosophers would rub elbows across our 3,280 acres of protected natural landscapes. Sixty beds meant people settled in and thought.

A trio of artists began visiting and contemplating appropriate activities. Brent Bucknum, an eco-design engineer involved in our facility planning. Freya Bardell and Brian Howe of GreenMeme, sculptors working at the intersection of art and ecology. We found ourselves collaborating on a competition created by the City of San Jose: the Climate Clock.

The premise was to design a landmark public artwork that would integrate Silicon Valley's measurement, data management, and communications technologies to help people understand and act on climate change. We were one of three finalists selected from an international pool.

Our proposal centered on a deceptively simple insight. If we had to reduce eco-systemic health down to one biological indicator that will change dramatically over the next hundred years, it would be the oak woodlands. The lack of regeneration and the loss of the ecosystem to sudden oak death remains a mystery to many biologists, though most believe it is linked to acidification of soils. A climate clock might outlast two-hundred to three-hundred year old California Blue Oaks. The oak and other fluxes in regionally specific biodiversity could become a visually and scientifically powerful instrument for monitoring climatic change.

We proposed a "wired wilderness"—a mesh network of sensors reading the pulse of the reserve, transmitted to a public installation in downtown San Jose. Visitors would enter through a tunnel that disassociated them from their surroundings, emerging into a virtual panoramic view of an oak woodland preserve nine miles from the center of the city but worlds away. A juxtaposition between digital and analog ecologies.

The central feature would be a scientific and visual study of a cluster of young oak trees and the lichen community adorning them. Lichen diversity correlates dramatically with air quality and human health. William Heydler first discovered this correlation while walking the streets of Paris in the 1860s—less lichen grew near industrial centers, more varieties on the rural edge. A century and a half of subsequent research confirmed certain lichen species link to specific pollutants: NOx, SOx, PCBs, CO.

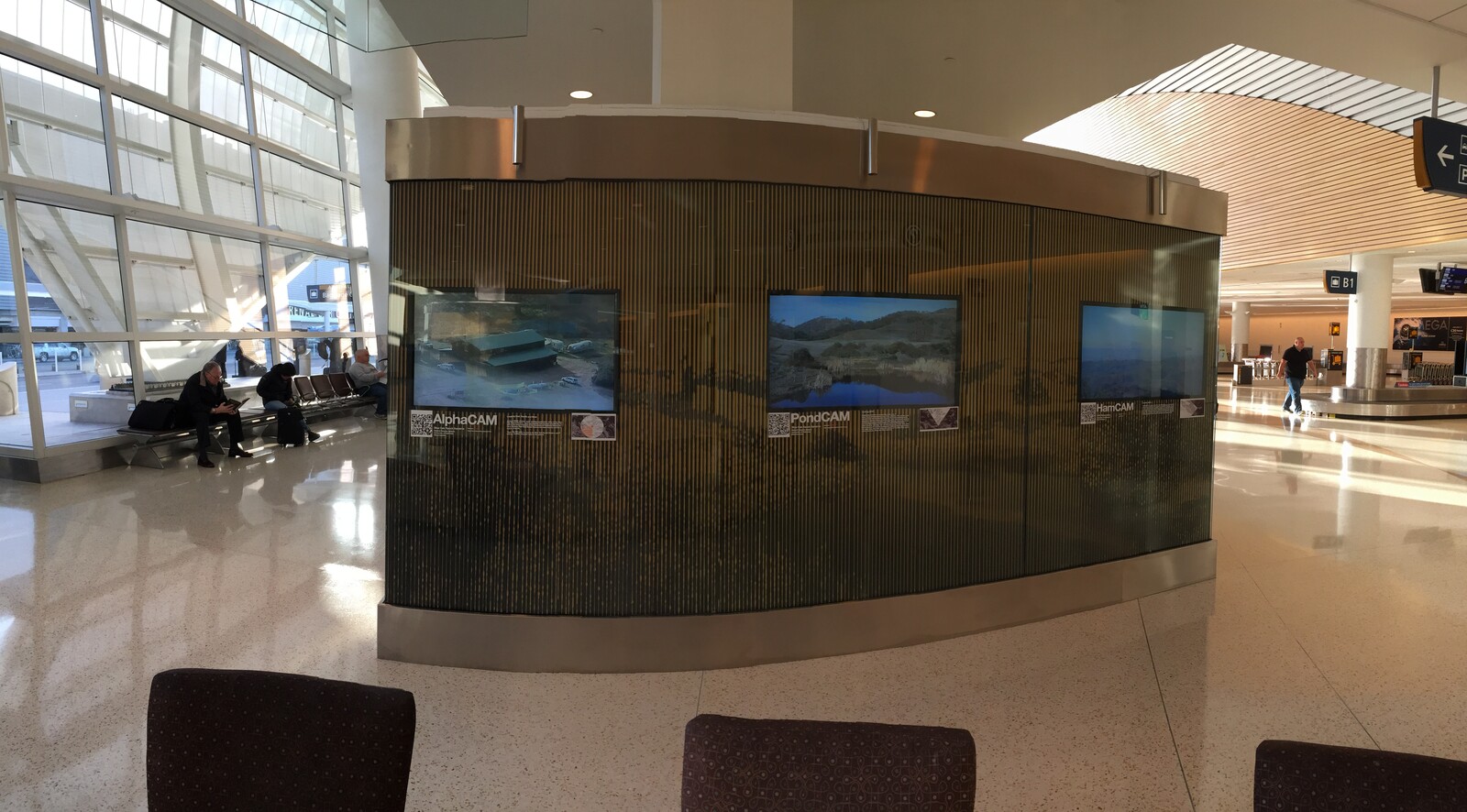

We did not win the competition. But the city was impressed enough to provide a mini-grant for a scaled implementation: a three-node phenology cameras broadcasting from Blue Oak Ranch to a custom exhibit in the San Jose Airport baggage terminal.

For two years, travelers waiting for luggage encountered a window into the reserve. A persistent observation point. Continuous. Patient. Broadcasting ecological time to people who had no choice but to wait and watch.

Hundreds of thousands of people encountered that oak woodland. The twenty-minute wait for a suitcase became a glimpse of a system operating on a two-hundred-year arc. That's science communication at a scale most field stations never achieve.

The Climate Clock was never primarily about displaying data. It was about making ecological timescales cognitively accessible to humans who think in minutes and days. A temporal translation device.

The idea clock is the same problem turned inward.

Ideas have timescales we don't naturally perceive. Some germinate in minutes. Some require years of vernalization before they can flower. Some need dormancy. Some fruit only once. Some are perennial. Without instrumentation, we can't see our own cognitive seasons. We mistake a fallow period for failure. We force production during dormancy. We miss the readiness signals.

In my morning dialogue with Claude, a term emerged that neither of us possessed at five AM: cognitive phenology.

The phrase works because phenology already concerns preparedness and timing. When does the organism become receptive? When are conditions aligned for the event? The naturalist's mind has its own bud burst, its own migration readiness, its own dormancy periods. Reading serves as photoperiod—the intellectual light exposure that triggers developmental transitions in attention and perception. My quotes database, my book collection, my document archive—these aren't just possessions. They're the phenological record of a prepared mind developing over fifty years. When did systems thinking vocabulary enter my writing? When did certain sources go dormant? Are there phase transitions visible in the sequence, or gradual drift?

For years I have been developing what I call the Macroscope—an integrated framework for observation across four domains: EARTH, LIFE, HOME, and SELF. The SELF domain has accumulated as a hodgepodge of disparate concepts: quotes, images, genealogy, health metrics, reading notes, family anecdotes. Cognitive phenology provides the spine. Not a taxonomy that sorts fragments into bins, but a temporal logic. What season does each fragment represent? What was coming into bloom, what was dormant, what was the intellectual weather?

Wikipedia, seen through this lens, is not a reference. It is a living temporal record of collective human attention. Every edit timestamped. Every article's history a stratigraphy of cultural cognition. The deletions and revisions and edit wars—that's the metabolism of knowing, made visible.

Hari Seldon called his cover story the Encyclopedia Galactica. The Foundation's surface project that justified gathering minds on Terminus while the real work of psychohistory proceeded in secret. Wikipedia is the Encyclopedia Galactica we actually built. Crowdsourced, messy, contested, alive. Not curated by a Foundation but emergent from collective attention. That's half of what we need—the knowledge substrate.

The other half comes from Asimov's other great fictional architecture.

If cognitive phenology is the observation—tracking the seasons of mind, recognizing readiness, understanding dormancy—then cognitive poetry is what emerges from that prepared awareness. The practice of making with ideas as medium. Not argumentation, not analysis, not information transfer. Composition. The patterns that rhyme across domains, caught and shaped into something that coheres aesthetically before it coheres logically. Phenology watches. Poetry arrives when the watching has prepared the ground.

The Climate Clock watched one thing deeply—an oak woodland across seasons and years. The Wiki-Lyrical Engine samples many things shallowly—the chaotic breadth of human knowledge in random collision. These are complementary instruments. Depth and breadth. Persistence and surprise.

A research paper crossed my desk yesterday that provides unexpected context. Yoel Fink's group at MIT published in Nature describing a complete computer embedded in a textile fiber—sensing, memory, processing, and communication unified in a thread thin enough to be woven into ordinary garments. The fibers run individual neural networks, share only classification probabilities rather than raw data, and achieve high accuracy through federated consensus among partial observers.

The architecture suggests where embodied idea clocks might eventually live. Not as external devices but woven into the fabric of daily life, coupled to physiological state, the body's clock entrained with the mind's clock. The cognitive prosthesis becoming integrated perception.

In I, Robot, Detective Spooner demands of the robots: "Can you write a symphony? Can you turn a canvas into a beautiful masterpiece?" The questions assume creativity as the threshold of mind. But Sonny—the robot who will prove singular—answers differently. He dreams. A recurring image: standing on a hill, leading others to freedom. He doesn't know what it means. The dream arrived before understanding.

What we're building is a dream simulator. Not a claim about consciousness—but an architectural conjecture. The accumulation buffer models exposure. The sleep phase loosens temporal coherence. The hypnopompic prompt catches the machine in transition, before full coherence clamps down on possibility. We're not asking the engine to write symphonies. We're asking it to dream, and to share what rhymed in the dark.

From Asimov's two great visions—the Encyclopedia Galactica that preserves collective knowledge and the robot whose dreams mark his emergence—we draw the architecture of the Wiki-Lyrical Engine. Wikipedia provides the substrate. The dream provides the mechanism.

But that's future work. Today we built the Wiki-Lyrical Engine.

By mid-morning, the system was operational. A LAMP stack on the Galatea server. Wikipedia's random article API feeding a buffer. Claude processing the accumulated fragments through a hypnopompic prompt. An admin panel with an "Activate Dreaming" button that fills the buffer and nudges the engine awake in a single action.

The human remains in the loop. I decide when to wake the machine. This matters. The distinction I've been drawing between centaur and reverse centaur—human head directing machine body versus human as accountability sink for machine decisions—plays out in a button click. The engine accumulates and processes, but the nudge is mine.

The first dream emerged from twelve Wikipedia fragments: pterodactyls, Turkish dams, Korean independence figures, protein folding, Icelandic geography. The what-if asked whether medieval Icelandic learning centers might have developed elemental musical notation decodable through protein folding algorithms. Absurd on its face. But the collision is the point—not the plausibility of the synthesis, but the reaching.

The second dream collided quadratic formulas with double-curvature concrete arch dams with DNA nanotechnology. The what-if: could the mathematical precision of dam engineering inform self-assembling DNA structures that fold according to modified quadratic equations?

Neither hypothesis will survive contact with disciplinary expertise. That's not the function. The function is to produce questions that wouldn't otherwise be asked. To make visible the shape of what's not being thought. The engine doesn't know anything. It juxtaposes, and waits for recognition.

Three forms, same buffer. The limerick forces comedic compression—rhythm, rhyme, absurdity. The haiku forces stillness—two images placed beside each other with no explanation, letting the cut do the work. The what-if forces propositional reach—beginning always with those two words, pushing toward novelty.

Some mornings the limerick will resonate. Some mornings the haiku. The what-if might fail repeatedly, then suddenly produce something that sends a curious mind to the literature.

You don't build an idea clock from theory of ideation. You build it from observation of ideation, the way a naturalist would. You instrument the process, run it, watch what emerges, refine conditions, remain humble about mechanism.

This morning's dialogue was a demonstration of its own subject. I woke with a question from the dream state. The terms that emerged—cognitive phenology, cognitive poetry—neither of us possessed at the start. They arrived from collision, from juxtaposition, from prepared recognition meeting unexpected pattern. By afternoon, the engine existed. By evening, it had dreamed twice.

The clock doesn't need to know how it works. It just needs to produce.

The dreams accumulate now in a public ledger. Anyone can visit, watch the what-ifs pile up, find their own resonance in the collisions. The cognitive phenology becomes observable—not just mine, but the engine's. What patterns emerge over weeks, months? Do certain collision types produce more generative what-ifs? Does the limerick quality vary with buffer size?

We'll find out. The instrument is running. The data will accrue.

And every time we nudge it awake, it hands us what rhymed in the dark.

References

- Chen, A. (2013). "Wired Wilderness." Living on Earth, Public Radio International. https://www.loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=13-P13-00003&segmentID=7 ↗

- UC Blue Oak Ranch Reserve. University of California Natural Reserve System. https://blueoakranch.ucnrs.org/ ↗

- Hyphae Design Laboratory. (2015). "UC Berkeley Blue Oak Ranch Reserve." https://www.hyphae.net/projects/blue-oak-ranch-reserve ↗

- Bardell, F., Howe, B., Bucknum, B., & Hamilton, M. (2009-2011). Wired Wilderness. Greenmeme / City of San Jose Cultural Affairs. https://www.greenmeme.com/art/crosby-nursery-7xeg2-lh4ps-ka7ae ↗

- Hamilton, M. P. (2025). "Wiki-Lyrical Engine Protocol: An Autonomous Cognitive Poetry Generator." Canemah Nature Laboratory Protocol CNL-PR-2025-019. https://canemah.org/archive/document.php?id=CNL-PR-2025-019 ↗

- - City of San Jose Office of Cultural Affairs. (2008). "Climate Clock Design Competition Press Release." September 25, 2008. ↗

- - Gupta, N., Cheung, H., Payra, S., et al. (2025). "A single-fibre computer enables textile networks and distributed inference." *Nature*, 639, 79-86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08568-6 ↗