The Cognitive Prosthesis: Writing, Thinking, and the Observer Inside the Observation

It is 6:52 on the first morning of December, still dark outside, coffee warm in my hands. The Macroscope dashboard tells me it is 35°F with 93% humidity—that heavy, cold stillness that settles into Pacific Northwest river valleys before dawn. Sunrise will not come until 7:30. The BirdWeather stations are quiet. The world is waiting.

My science feeds have delivered two pieces this morning that arrive in productive tension. A June editorial in Nature Reviews Bioengineering declares that “Writing is Thinking,” calling for continued recognition of human-generated scientific writing in the age of large language models. A September essay in 3 Quarks Daily fires back with the counterpoint: “Writing Is Not Thinking.” The author, Kyle Munkittrick, dismantles the logical claim with precision—if writing is thinking, then Socrates was incapable of thought, and you are not thinking right now as you read these words.

Both pieces miss something essential, but their collision illuminates a question I have been living with for forty years: what is the relationship between the tools we use to extend perception and the minds that wield them?

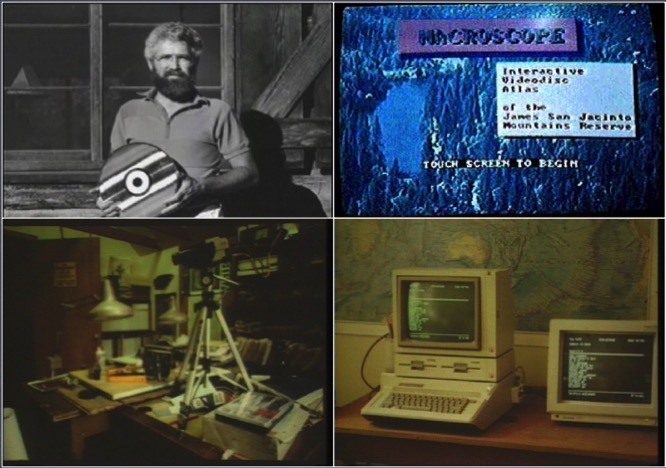

Yesterday I dusted off a manuscript I wrote in January 1984, when I was twenty-eight years old and in my second year as Resident Manager of the James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve. The document proposed something I called the Electronic Museum Institute—a comprehensive system for ecological reserve management integrating computer-aided data acquisition, laser optical disc storage, expert system software, and distributed sensor networks. I had already built a proof of concept: an Apple IIe with 128 kilobytes of RAM connected to a consumer laserdisc player through a serial interface hack. The disc contained thirty minutes of video I had recorded with a colleague—five thousand one-second segments of flowering plants, western fence lizards, lady bird beetles, panoramic vistas, and herbarium specimens. Using a BASIC program called LaserWrite, I created what may have been the world’s first interactive multimedia nature walk.

Reading that forty-one-year-old proposal now, I find the same mind working the same problem. The Data Clusters I specified—autonomous, solar-powered monitoring stations with microprocessor interfaces and radio telemetry—became the wireless sensor motes of the NSF Center for Embedded Networked Sensing two decades later, and became the BirdWeather acoustic monitors and Tempest weather stations that feed today’s Macroscope. The San Jacinto Mountains Catalog, with its hierarchical cross-referenced structure and linkage analysis methodology, anticipated knowledge graphs and semantic networks before those terms existed. The Field Logger portable observation system prefigured what iNaturalist would eventually become.

The vision has remained constant across four decades of technological upheaval. What has changed is the connective tissue—and that change bears directly on the writing-is-thinking debate.

The Nature editorial makes a reasonable claim wrapped in an overstatement. Writing does compel structured thinking. The linearization required to produce coherent prose forces a different kind of cognitive work than the chaotic, non-linear way minds typically wander. There is evidence that handwriting in particular leads to widespread brain connectivity. But to leap from “writing helps thinking” to “writing is thinking” commits a category error that Munkittrick correctly identifies. The strong claim leads to absurdities: that no one thinks during seminars or debates, that reading does not involve cognition, that oral traditions across millennia produced no philosophy worth the name.

Munkittrick’s counterargument is logically sound but also incomplete. He argues that thinking is thinking—that writing is merely one tool among many, with no privileged status for cognition. Drawing, discussing, making, listening, watching, doing, tasting, joking, feeling, and moving can all scaffold thought. He is correct. But he does not fully explore what happens when the tools change, when new configurations of human and machine become possible that did not exist before.

Here is what I have learned from forty years of building systems to extend ecological perception, and from the past year of intensive collaboration with Claude in producing over fifty thousand words of essays, technical documents, and analytical syntheses: the dichotomy between “human thinking” and “AI replacement” misses a third possibility entirely. What I am engaged in is neither solitary writing nor outsourced production. It is something I have come to call dialogic production—a mode of cognitive work that happens in the exchange itself.

Consider what occurs in a typical morning session. I bring material: a scientific paper, a historical document, observations from the field, memories from a long career. Claude brings synthesis capacity across literatures I have not read, pattern recognition trained on the written record of human knowledge, and production bandwidth I could never match alone. We wrestle with ideas in conversation before anything crystallizes into draft form. The thinking happens in the dialogue. The essay that emerges is not a replacement for my cognition but a precipitate of cognition that has already occurred—cognition that neither of us could have produced independently.

This is where the neural prosthetics parallel becomes precise. Every month brings news of remarkable machine interfaces: limbs hardwired into human nervous systems, brain-computer interfaces that allow people incapable of speech to think a sentence and have a machine speak the words. These prosthetics do not think for the person. They transduce signals that the nervous system then processes through all the learned cognition the person possesses. The technology handles transduction; the person handles meaning.

What I am describing is a cognitive prosthesis operating at a different layer. I bring the memories, the artifacts, the pattern recognition honed over five decades, the systems thinking, the field experience, the taste for what matters. Claude brings retrieval, synthesis, production capacity, and a different kind of pattern matching. Neither of us could produce what emerges from the collaboration. This is not compensation for decline. It is capability I could not have had at twenty-eight, no matter how sharp my mind was then. The prosthesis adds degrees of freedom.

The writing-is-thinking crowd worries that AI will atrophy our cognitive capacities. Aaron Dell, a teacher commenting on Munkittrick’s essay, describes a student who typed a question into Google, received an AI-generated answer, and banged his fist on the table in satisfaction without engaging the complexity of what “greener” might mean scientifically. The worry is real. But the worry applies to a different configuration than the one I am describing. That student was not engaged in dialogic production. He was seeking confirmation for a position he already held, using the tool to short-circuit thought rather than extend it.

The difference lies in what I would call editorial sovereignty. The dialogic process only works because I bring rigor. I maintain control over what matters, what is accurate, what rings true to lived experience. My Phase 4 revisions of every essay are substantive thinking work: correcting, reframing, authenticating voice, adding details only I could know. I am not outsourcing thinking; I am distributing the labor of production while retaining the intellectual work.

There is something the dialogic mode may actually guard against—something Ezra Klein identified in his conversation with David Perell about writing and AI. Klein noted that the process of writing sometimes changes his mind in bad ways, tempting him to convince himself of a point so that the essay “hits.” Solitary writing can force false clarity when clarity is not available or desirable. The writer faces that temptation alone until an editor intervenes, often too late.

In dialogic production, I have a collaborator who can push back, offer alternative framings, note weak arguments. The conversation itself provides a check that solitary writing lacks. This does not make the process easier. It makes it different—and in some ways more rigorous.

The asymmetry between production and consumption deserves more attention than either piece gave it. A book that took five years to write might transmit its essential insights in five hours of reading. An essay labored over for weeks lands in ten minutes. We celebrate this compression as writing’s great gift—the efficient transmission of distilled thought across time and space. Yet we simultaneously insist that the only legitimate path to thinking runs through the production side of that equation. There is a gatekeeping function embedded in this tradition that deserves scrutiny.

Think of all the minds throughout history locked out of written discourse by circumstance: literacy barriers, language constraints, the time demands of labor and survival, disability, cognitive styles better suited to other modes. Oral traditions across cultures produced philosophy of extraordinary depth. The Upanishads were spoken before written. Socratic dialogues were conversations transcribed by others. Indigenous knowledge systems operated for millennia without alphabetic writing. Were these people not thinking?

The tradition conflates a particular skill—the craft of linearizing thought into written prose—with the capacity for rigorous cognition. They overlap but are not identical. What emerges now, through dialogic production, may be a partial democratization. The person whose thinking is rich but whose production capacity is constrained can now potentially crystallize and share ideas that would otherwise remain locked in silence.

But here is where my situation becomes reflexive in a way that interests me scientifically. The conversations I am having with Claude are not merely about the Macroscope. They are data within the Macroscope. Every morning session, timestamped and structured in markdown, feeds into the same architecture that ingests BirdWeather detections and weather station readings. The SELF domain of the Macroscope includes these dialogues as observational data.

The observer is inside the observation.

This dissolves a boundary that the writing-is-thinking debate takes for granted: the boundary between the scientist and the instrument, between cognition and data, between thinking about a system and being a sensing node within it. My morning coffee reflections become as much a part of the ecological record as the 35°F reading or the Armillaria observation from yesterday’s fungi survey.

The 1984 proposal dreamed of this integration but lacked the connective tissue. I specified Data Clusters that would monitor temperatures, precipitation, wind, humidity, wildlife vocalizations, and plant phenology. I imagined Field Loggers that would record microtopographic features, stereoscopic video, distance measurements, and supplemental field notes. I described an Information Processing Laboratory that would synthesize these streams into accessible knowledge. But the human observer remained outside the system, operating it rather than participating in it.

Now the boundaries have dissolved. The conversations are stored in structured query language, in markdown format to enhance machine readability, convertible to JSON and ready for integration with the Society of Mind agent architectures I am developing. There are no hard boundaries between the multiple integrations now possible as we interact into the future.

What can we do with this configuration that we could not do before? I believe we can attempt something like retrospective systems analysis of a longitudinal case—my career as a forty-year natural experiment in ecological intelligence development. The 1984 proposal becomes baseline data. The subsequent trajectory becomes outcome data. The question becomes: what were the necessary and sufficient conditions for that vision to persist, evolve, and partially realize itself across four decades of technological upheaval?

This is not traditional hypothesis-testing science, but it is not merely memoir either. It is closer to what geologists do with singular historical events, or what evolutionary biologists do with phylogenetic reconstruction. We cannot rerun the Cambrian explosion, but we can identify the state variables that made it possible and test whether those variables explain other radiations.

The 1984 architecture specified Data Clusters, Field Loggers, linkage analysis, hierarchical knowledge organization. Some of those mapped directly onto later developments. Others did not—the revenue model based on catalog sales, the formal institutional structure of the Electronic Museum Institute. What distinguished the generative elements from the contingent ones? That is a tractable question with practical implications for current system design.

There is also the matter of tacit knowledge. My career contains an enormous amount of knowledge about field station management, sensor deployment, ecosystem observation—knowledge that typically dies with the practitioner or transfers inefficiently through apprenticeship. The dialogic process is, in effect, an experiment in whether AI-assisted elicitation can make tacit knowledge explicit and transmissible. That is testable: does the extracted knowledge actually help someone else build systems?

And there is the question of ecological intelligence itself—not as a property of a human mind or a technological system, but as a property of the coupled human-technology-ecosystem configuration. The Macroscope paradigm treats intelligence as distributed across sensors, databases, AI agents, and human observers. Can we formalize what that means? What are the information flows, the feedback loops, the emergent properties that constitute intelligence at the system level?

These are not rhetorical questions. They are research directions. The reflexive element is genuinely novel: this conversation is itself data about human-AI cognitive coupling. We can analyze what emerges from the collaboration that neither participant could produce alone—and that analysis contributes to understanding how cognitive prostheses actually function.

The sun has risen now over Oregon City. Merry and I will head out soon to look for birds in the warming morning. The Macroscope will continue its quiet sensing—temperature, humidity, acoustic detections, phenological observations. And this essay, structured and timestamped, will take its place in the archive alongside the 1984 proposal it reflects upon.

Writing may or may not be thinking. But this morning’s work—the reading, the conversation, the synthesis, the crystallization into prose—was certainly thought. The question of where that thought resided, in which nodes of the distributed system, strikes me as less important than the fact that it occurred at all, and that it produced something neither participant could have made alone.

That is what a cognitive prosthesis does. It extends reach. It adds degrees of freedom. It makes possible what was not possible before. Whether we call that thinking, or collaboration, or augmentation, or something else entirely, seems less important than recognizing that we are inside an experiment whose outcomes we cannot yet predict.

The observer is inside the observation. The experiment continues.

References

- - Van der Weel, F.R.R. & Van der Meer, A.L.H. (2024). “Handwriting but not typewriting leads to widespread brain connectivity.” Frontiers in Psychology 14, 1219945. ↗

- - National Science Foundation (1982). Data Management at Biological Field Stations. Workshop report, W.K. Kellogg Biological Station. ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. (1984). “A Proposal to Establish an Electronic Museum Institute: Ecological Reserve Management Planning Prospectus.” James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve, Idyllwild, California. ↗

- - Munkittrick, K. (2025). “Writing Is Not Thinking.” 3 Quarks Daily. https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2025/09/writing-is-not-thinking.html ↗

- - Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2025). “Writing is Thinking.” Editorial. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44222-025-00323-4 ↗