I Cannot Warm You If Your Heart Be Cold

I read this morning about Neanderthals making fire in Suffolk, England, 400,000 years ago. Archaeologists at a site called Barnham found the telltale evidence: baked clay forming a half-meter hearth, flint hand axes shattered by intense heat, and two small fragments of iron pyrite—fool’s gold—that someone had carried to this woodland pond from elsewhere, understanding that when struck against flint, it would throw sparks into waiting tinder.

The pyrite is what clinches it. In 37 years of geological surveys across 20 sites in the region, examining 121,000 individual rock specimens, researchers had never found pyrite. The only pyrite ever recovered appeared in that single layer, beside that single hearth, among those fire-cracked tools. Someone knew what they were doing. Someone had mastered fire 350,000 years before our species even emerged in Africa.

The paper describes how fire created “illuminated spaces that became focal points for social interaction.” I sat with that phrase as dawn approached outside my window in Oregon, because I have spent my entire life in such spaces, and much of my career deliberately creating them.

My parents loved to camp. This was the 1950s and 60s, when a family vacation meant loading the station wagon and heading for state parks where the fire ring waited at every site. I learned early what every child learns around a campfire: that the circle of light creates a temporary architecture of belonging, that the darkness beyond the firelight makes the warmth within more precious, that stories told beside flames lodge deeper in memory than stories told anywhere else.

I joined the Boy Scouts and perfected my campcraft—the proper construction of a fire lay, the patience required to coax flame from friction, the responsibility of tending coals through a long night. These were not merely outdoor skills. They were initiations into an ancient human practice, though I didn’t understand it that way at the time.

In my twenties, I worked as a seasonal park aide at Round Valley in the San Jacinto Wilderness. Each week, I gathered backpackers around the campfire for evening programs—songs, stories about the animals whose territory they were passing through, accounts of the Cahuilla people who had lived on this mountain for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. I learned then that fire creates a particular quality of attention. People listen differently in firelight. They become, for a little while, one group instead of separate individuals.

In 1982, I became director of the James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve, a University of California field station high in the mountains east of Los Angeles. The reserve was established in 1966 when Harry and Grace James donated their property to the university, accepting a life estate in exchange for seeing their beloved land protected for teaching and research.

Harry Claiborne James had built Lolomi Lodge—named for the Hopi word for “peace”—from locally cut logs in the 1940s. He had been a friend of Ernest Thompson Seton, had founded his own Western Rangers youth organization, had run the Trailfinders School for Boys that sent nearly 40,000 young men into the mountains over four decades. Harry understood what I was only beginning to understand: that wild places require not just protection but gathering spaces, focal points where human community can form around shared experience of the natural world.

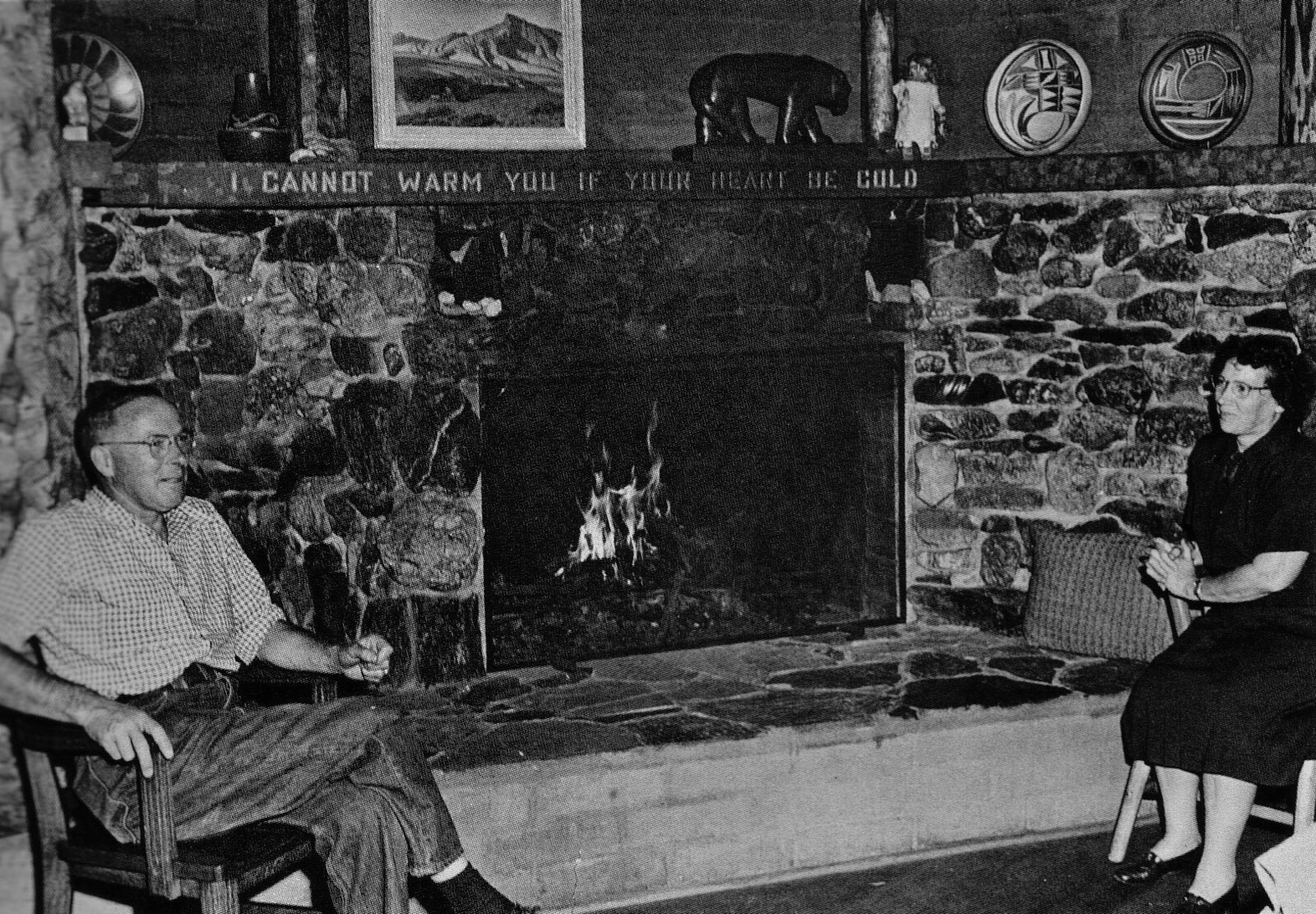

Carved into the wooden mantle above the hearth in Lolomi Lodge is an inscription I lived beneath for 26 years: “I cannot warm you if your heart be cold.”

It’s a challenge and an invitation. The fire offers, but cannot compel. The human must arrive ready to be warmed. I thought about that inscription constantly—when I welcomed new graduate students to the reserve, when visiting researchers gathered in the evening after fieldwork, when the winter storms drove everyone inside to the great room where Harry’s fireplace still burned.

I built a proper fire circle at the James Reserve, a deliberate piece of social infrastructure. I built another at Blue Oak Ranch Reserve when I helped establish that station years later. These were not afterthoughts. They were as essential to my conception of a field station as the laboratory space or the specimen collections. A field station without a fire circle is just a building with data.

Among the researchers who came to the James Reserve in those years was a graduate student from UC San Diego named Pamela Yeh. She was studying the dark-eyed juncos that hopped through the forest understory—small gray sparrows with pink bills and white tail feathers that flash when they fly. Pamela spent seasons on her hands and knees, finding ground nests hidden in the leaf litter, making meticulous measurements of bill length and bill depth, tarsus length and body mass.

I remember her patience, her precision, the quiet dedication that marks researchers who will go on to build careers. She is now faculty at UCLA with an affiliation at the Santa Fe Institute, and this week she published a paper in PNAS that made me smile with recognition.

The paper concerns what happened to Los Angeles juncos during the COVID-19 pandemic. The UCLA campus population of juncos had, over 40 years of urban living, developed bills that were shorter and thicker than their wildland counterparts—an adaptation, researchers believed, to exploiting human food waste, the dropped French fries and scattered crumbs of a busy university campus.

Then came the lockdowns. For 18 months, the campus fell quiet. Dining halls closed. Students stayed home. And the juncos that hatched during this “anthropause” grew up with bills that looked nothing like their urban parents—they looked like wildland birds. They looked, in fact, like the juncos Pamela had measured decades earlier in the San Jacinto Mountains.

More remarkable still: when the students returned, when the dining halls reopened and the food waste resumed, the bills shifted back. Within two years, the juncos had returned to their urban morphology. The selective pressure was that immediate, that strong.

I read this paper and thought about baseline, about reference, about what we preserve when we preserve wild places. The James Reserve juncos—descendants of the birds Pamela measured all those years ago—are now the control group in a natural experiment about human influence on evolution. They are the living record of what “before” looks like. Without wildland populations to compare against, we couldn’t know what the anthropause revealed.

My partner Merry has lived at Owl Farm in Bellingham for decades. Her fire pit predates our friendship; she came to this relationship already fluent in the language of hearth-tending. Her home is warmed by a wood stove that I joyfully tend when I visit each month, learning its particular drafts and dampers, the rhythm of her wood supply. There is an old form of care in keeping someone’s home warm while they go about their day.

Here in Oregon City, in the McLoughlin Historic District, I live for the first time in my adult life in a home without a fireplace. It is a small loss and a real one. On mornings like this one—53 degrees, 100% humidity, the darkness thick before a December dawn five days from solstice—the absence registers.

I compensate. The monthly commute north includes, among its pleasures, the return to fire. The wood stove waiting. The fire pit for longer evenings when weather permits. Owl Farm holds what Oregon City lacks.

Four hundred thousand years ago, someone at Barnham understood that pyrite and flint, properly struck, would give them fire whenever they needed it. They no longer had to wait for lightning, no longer had to hope for wildfire they could capture and tend. They could create the illuminated space themselves, summon the gathering point, push back the darkness.

We are still doing it. The researchers at the British Museum call this discovery evidence of “a pivotal moment in human development.” They speculate about fire’s role in brain evolution—our metabolically expensive brains requiring cooked food to fuel them—and about the social complexity that fire enabled, the evening gatherings that became sites for planning, storytelling, and the strengthening of group bonds.

I think about the thousands of fires I have built across 60 years. The childhood campfires that formed me. The ranger programs where backpackers became, briefly, community. The field station fire circles that gathered students and faculty into conversation that went deeper than any conference session. The wood stove at Owl Farm that warms more than the room.

“I cannot warm you if your heart be cold.” Harry James carved that challenge into his hearth nearly 80 years ago. But the work of fire has always been to help cold hearts warm—to create the conditions where warmth becomes possible, where the architecture of belonging can form around a shared center.

The Neanderthals at Barnham knew this. Every human culture since has known it. And now, 400,000 years after someone first struck pyrite against flint in that Suffolk woodland, I sit in the pre-dawn darkness reading about their fire, thinking about mine, warmed by the long continuity of this most human practice.

The juncos will adapt to whatever we give them. That’s the lesson of Pamela’s paper—they respond to our presence with remarkable speed, reshaping themselves to the world we make. But somewhere in the San Jacinto Mountains, in the forest I tended for 26 years, the wildland juncos still carry the older pattern. The baseline. The memory of before.

We need those reference populations. We need the wild places that hold them. And we need the fire circles—literal and figurative—where we can gather to remember what we’re trying to protect, and why it matters, and how very long we’ve been warming ourselves and each other against the darkness.