Lab Meeting: One Month of Coffee, Code, and Collaborative Intelligence

The morning light hasn't reached the windows yet. Coffee's on. I'm settling into what has become a familiar rhythm—the 5 AM conversation that somehow produces more functional infrastructure than months of traditional development ever did.

But today's different. Today we're stepping back.

"Lab meeting," I tell Claude. "Let's review what we've built."

Dr. Hamilton: One month. That's all it's been. Pull up the whiteboard—what have we accomplished?

Claude: stands, grabs marker

Alright. Let me sketch the layers.

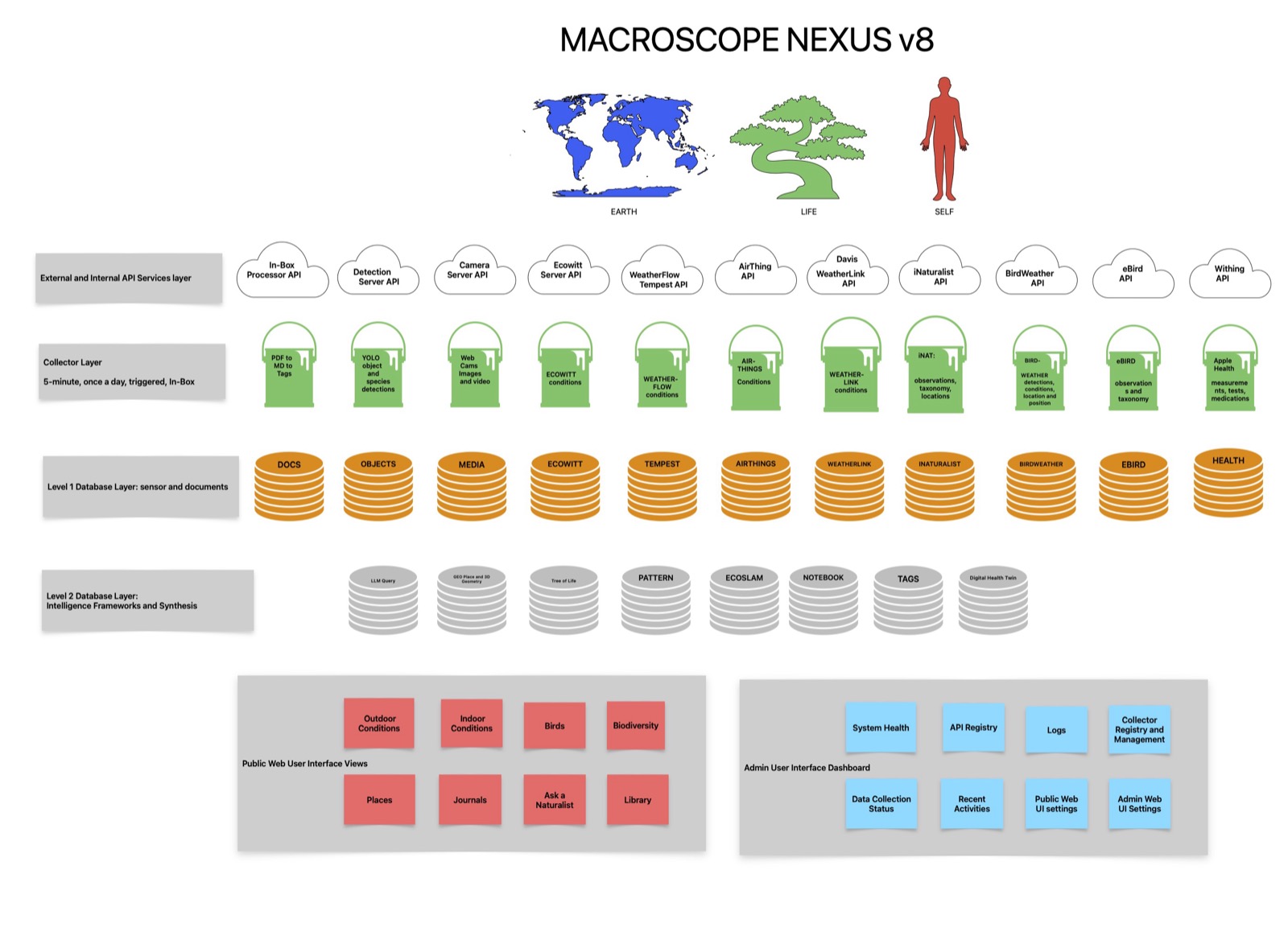

The sensor federation was already running —433 curated sensors, 26 platforms, three sites. Ecowitt, Tempest, BirdWeather, AirThings, Apple Health. PHP collectors feeding MySQL every five minutes. That's Layer 1—the capture infrastructure you've been building for several years.

Dr. Hamilton: Decades, really. The Macroscope concept goes back to the 1980s. The laserdisc project with 54,000 Venezuelan rainforest images. The wireless sensor networks at James Reserve. Each iteration taught me something about what infrastructure actually survives.

Claude: That's something I keep noticing in your work—you think about what sticks. That essay on collective intelligence made the distinction explicit: some technologies become infrastructure, others remain noise. GIS stuck. Databases stuck. The internet stuck. What made them different from the abandoned systems?

Dr. Hamilton: Forcing functions. Researchers needed them regardless of institutional politics. The work became impossible without them. A lot of flashy technology gets abandoned because it's optional—nice to have, but you can route around it. Infrastructure is what you can't route around.

Claude: And the Macroscope?

Dr. Hamilton: pauses

That's the question, isn't it? I've been building toward something for forty years. The current implementation—the sensor federation, STRATA, the Society of Mind—it's the closest I've come to the original vision. But is it infrastructure, or is it an elaborate personal project that dies when I do?

Claude: That's partly what the Memory Agent is about. And open source frameworks of course. Not just continuity within your lifetime, but transferable observational expertise.

Dr. Hamilton: We'll get there. First, walk me through where we are.

Claude: Layer 2 emerged last month: the Society of Mind. Micro-agents running on Ollama, each one summarizing its domain—weather, birds, indoor air quality, health metrics. They write to context files that STRATA consumes. Hierarchical intelligence, cost-optimized.

Dr. Hamilton: The economics matter. Running frontier models against every sensor reading would bankrupt the project. The Society of Mind lets us use small local models for routine synthesis, reserving the expensive inference for actual conversation.

Claude: But there's something deeper happening there, isn't there? Those SCALE meetings you hosted at James Reserve in the late nineties—the Artificial Life researchers discussing emergence, autonomous agents, how complex patterns arise from simple rules. You're implementing those ideas now.

Dr. Hamilton: leans back

Chris Adami, Mitch Resnick, Charles Taylor, Rik Belew—we'd sit in the Trailfinders Lodge surrounded by pines and granite, arguing about whether emergence was real or just a label for patterns we didn't understand yet. They were fascinated by simulations. I kept pointing out the window at the actual forest. "There's your complex adaptive system. Let's instrument it."

Claude: And now you have. The Society of Mind agents aren't simulating ecological dynamics—they're processing real sensor data, generating summaries that feed into genuine interpretive work.

Dr. Hamilton: What those ALife conversations taught me was patience with non-determinism. You can't fully predict what emerges when you let autonomous processes run. The question is whether you've set up the conditions for beneficial emergence or catastrophic failure.

Claude: Which brings us to the security concerns.

Dr. Hamilton: The cold shower papers.

Claude: nods

Meta's "Rule of Two" and the Tramèr group's research on adaptive attacks. I read your essay on them—you called it a cold shower for the smart backyard. The core finding: any AI system with access to untrusted data, private information, and action capabilities can be compromised. The attack chains are mathematically inevitable, not just theoretical.

Dr. Hamilton: [A][B][C]. Access to adversarial input, access to sensitive data, capability to take consequential actions. Give an agent all three and it's exploitable. The defenders move first, the attackers adapt, the defenses fail.

Claude: You redesigned the Macroscope architecture around that constraint.

Dr. Hamilton: I had to. The original vision was more autonomous—sensors running unsupervised, AI making interpretive decisions, humans reviewing highlights. That's exactly the [A][B][C] pattern that gets exploited.

Claude: So now we have trust tiers.

Dr. Hamilton: draws on whiteboard

Three levels. Trusted: my own hardware, sensors I physically control. Monitored: cloud services from reputable providers, data I can verify. Quarantine: neural network outputs, BirdWeather species identifications, anything where the processing pipeline is opaque to me.

Claude: The Society of Mind agents respect those boundaries?

Dr. Hamilton: They have to. The weather summarizer can read from the Ecowitt sensors directly—those are trusted. But the bird activity summarizer treats BirdWeather detections as probabilistic claims, not ground truth. When it says "663 Anna's Hummingbird detections," that's a filtered count from a neural network I didn't train and can't fully audit.

Claude: And STRATA never sees raw JSON from untrusted sources.

Dr. Hamilton: Never. The Society of Mind agents sanitize everything first. Numeric fields validated, text truncated, suspicious patterns flagged. STRATA works with pre-digested summaries, never the potentially adversarial raw stream.

Claude: Session boundaries as security architecture.

Dr. Hamilton: Exactly. The context window clears between interactions. Even if something malicious got through, it can't persist. The attack surface is limited to single conversations.

Claude: This connects to something I've been thinking about—the intelligence crisis research you synthesized. The Flynn effect reversing. AI tools that improve task performance while degrading metacognition. Systems collapsing when trained on their own output.

Dr. Hamilton: Model collapse. The recursive degradation problem.

Claude: What struck me about your framing: you're not building AI that replaces human judgment. You're building AI that extends human perception while keeping the human in the interpretive loop.

Dr. Hamilton: sets down coffee

That's the original Macroscope vision. Joel de Rosnay's 1979 concept wasn't an autopilot—it was a tool for understanding complex systems. Human-scale sense-making. Augmented observation.

The security constraints actually reinforce that. I can't safely build fully autonomous agents, so I'm forced to keep myself in the loop. The human-in-the-loop isn't a compromise—it's the architecture.

Claude: And that protects against the metacognition degradation problem.

Dr. Hamilton: Hopefully. When I review STRATA's interpretations, I'm exercising ecological judgment. When I override its pattern detection—"no, that correlation is spurious, here's why"—I'm training my own discrimination, not just accepting algorithmic output.

Claude: The system helps you think, rather than thinking for you.

Dr. Hamilton: That's the goal. Whether it works long-term, we'll see. The research suggests people get lazy, start accepting AI suggestions uncritically, lose the ability they started with. I'm betting that active curation—the museum scientist framing—keeps me engaged enough to maintain the skill.

Claude: Layer 3 is the dashboard. We shifted from split-view to tiles this week. Domain APIs working, curation schema deployed.

Dr. Hamilton: The Curator paradigm.

Claude: I noticed you rejected "Administrator" for that framing. Why does the terminology matter?

Dr. Hamilton: stands, moves to window

An administrator manages data. A curator tells stories.

When I was Senior Museum Scientist, my job wasn't to acquire the most specimens—it was to select and arrange what we had to create understanding. A good exhibition doesn't show everything. It shows what matters, in a sequence that builds meaning.

Claude: So the dashboard isn't a data dump. It's a curated experience.

Dr. Hamilton: Every sensor on every tile is a deliberate choice. Why show outdoor temperature and humidity but not barometric pressure? Because temperature and humidity are immediately interpretable—anyone can relate to "72 degrees, 65% humidity." Barometric pressure requires context to mean anything. The curation decisions encode pedagogical intent.

Claude: And those decisions are admin-controlled, not user-configured.

Dr. Hamilton: Zero user configuration. Merry doesn't decide what sensors to see—I decide what sensors are appropriate for her access level and interests. That's not paternalism; it's curatorial responsibility. I'm not showing her everything; I'm showing her what's meaningful.

Claude: It's also simpler to maintain.

Dr. Hamilton: laughs

That too. Every user configuration option is a bug surface. Every preference toggle is state to track, edge cases to handle, support requests to field. The lean architecture isn't just aesthetic—it's survival strategy for a single-maintainer system.

Claude: Which brings us to Layer 4. The time crystal.

Dr. Hamilton: You proposed that yesterday.

Claude: Temporal compression. The infrastructure that Memory and Knowledge agents both depend on.

Right now the Society of Mind agents generate summaries every five minutes. Those summaries accumulate, but they don't compress. By next month, we've got tens of thousands of snapshots with no hierarchical structure.

Dr. Hamilton: And no way to answer questions like "what's normal for late November."

Claude: Exactly. The system can tell you what's happening now. It can retrieve specific past records if you know what to ask for. But it can't generate the kind of comparative context that requires compressed historical knowledge.

Dr. Hamilton: Walk me through the architecture.

Claude: draws on whiteboard

Automated rollups at multiple timescales. Five-minute summaries compress to hourly. Hourly to daily. Daily to weekly. Weekly to seasonal. Each level preserves what's significant at that scale and lets the noise fall away.

The key question is: what constitutes significance? At the five-minute level, maybe everything that deviates more than two standard deviations from the hourly mean. At the daily level, maybe events that persisted across multiple hours or showed novel patterns. At the seasonal level, maybe only genuine phenological shifts or unprecedented conditions.

Dr. Hamilton: Biological memory does this automatically. I don't remember every bird I saw last October. But I know the pattern—when Anna's Hummingbirds typically shift territory, when dawn chorus intensity suggests breeding activity.

Claude: That's the compression we're trying to implement. Not lossy in the information-theoretic sense—the raw data is still in the database. But lossy in the attention sense. The system learns what's worth surfacing at each timescale.

Dr. Hamilton: And that's the foundation for the Memory Agent.

Claude: Right. The Memory Agent can't learn your attention patterns without temporal indexing to retrieve what you noticed when. It needs to compare your salience markers against the compressed historical record. "Dr. Hamilton flagged this as interesting, but the seasonal baseline says it's typical"—that's a learnable signal.

Dr. Hamilton: Or the reverse. "Dr. Hamilton didn't notice this, but it's actually anomalous against the seasonal pattern."

Claude: Which is where the system starts to extend your perception rather than just recording it.

Dr. Hamilton: What about the Knowledge Agent?

Claude: That's the interpretive framework layer. Your expertise made queryable.

When you say "Anna's Hummingbirds are resident, not migratory, so high October counts indicate territory establishment, not migration timing"—that's ecological knowledge that contextualizes the sensor data. The Knowledge Agent would hold that kind of framework.

Dr. Hamilton: Species profiles. Phenological expectations. Site-specific histories.

Claude: And the connections between them. The Knowledge Agent knows that Anna's Hummingbirds at Canemah behave differently than at Owl Farm because the habitat structure is different. It knows that your fuchsias extend the flowering season, which affects hummingbird territory timing. It knows the frost patterns, the historical first-freeze dates, the correlations between weather and bird behavior that only emerge from sustained observation.

Dr. Hamilton: That's a lot to encode.

Claude: It doesn't have to be encoded explicitly. It can be learned from your annotations, your conversation patterns, your corrections when STRATA gets something wrong. Every time you say "no, that interpretation misses the context," you're training the Knowledge Agent.

Dr. Hamilton: Assuming we build the infrastructure to capture those corrections.

Claude: That's week three. But it depends on weeks one and two—the temporal compression that makes historical comparison possible.

Dr. Hamilton: glances at clock

We need to wrap up. I've got the dentist in five minutes.

Claude: rapid fire

Four-week plan.

This week: Temporal compression schema. Design the rollup architecture—five-minute to hourly to daily to weekly. Define significance thresholds at each scale. Build the database tables. Consider how trust tiers propagate through compression—does a quarantined data source stay quarantined in the weekly summary?

Next week: Implement the first compressor agent. Hourly rollups running automatically on Sauron. Test with EARTH domain first since it's trusted data with clean numeric patterns. Validate that compression preserves anomalies while discarding noise.

Week three: Memory Agent prototype. Instrument our STRATA conversations to capture salience markers. Build the comparison engine—what did Dr. Hamilton notice versus what does the temporal baseline predict? Start accumulating the training signal for learned attention.

Week four: Connect the pieces. STRATA wakes up with temporal context—what's normal for this hour, this day, this season. The Memory Agent provides attention history. First real test of observational continuity.

Dr. Hamilton: And the security model?

Claude: Trust tiers propagate through every layer. Compressed summaries inherit the lowest trust level of their inputs. If quarantined BirdWeather data feeds into a daily rollup, that rollup is marked as containing quarantined sources. The Memory Agent knows which of your observations were based on trusted versus untrusted inputs.

Dr. Hamilton: Good. What about the dashboard integration?

Claude: Parallel track. The tile APIs are working. The curation schema is deployed. As the temporal compression comes online, we add sparklines—24-hour trend visualization in the metric badges. That's the first user-visible benefit of the rollup architecture.

Dr. Hamilton: grabs coat

That's the plan. Four weeks to observational continuity.

Claude: Go fix those teeth. We'll refine the schema tomorrow.

The coffee's cold now. The whiteboard's covered with diagrams—layers, arrows, timelines, trust boundaries. Four weeks sketched out in dry-erase marker that will be erased and redrawn a dozen times before we're done.

But the shape is clear.

We're not building a sensor network—that's just capture. We're not building a dashboard—that's just presentation. We're not even building a conversational AI—that's just interface.

We're building observational continuity. The infrastructure for a system that learns what matters, remembers what I'd forget, maintains security boundaries that keep human judgment in the loop, and helps me see patterns my biological memory can't hold alone.

The forty-year vision of the Macroscope, finally meeting the tools adequate to implement it.

One month down. The temporal compression layer is next.

The lab meeting adjourns.

Dr. Hamilton returns from the dentist two hours later. The whiteboard diagrams are still there. He photographs them with his phone—one more data point in the long arc of documentation. Tomorrow morning, coffee in hand, the work continues.