Linkage Propositions: A Semantic Explorer for Professor Troncale

I learned this week that Professor Len Troncale died on April 24th, surrounded by his family in Claremont, California. He was eighty-one. I found out the way we find out most things now—a search query returned his Wikipedia page, and the dates in the infobox had changed. Born 1943. Died 2025.

I had been researching his papers on General Systems Theory, looking for the intellectual genealogy of something I'd just built: a three-dimensional visualization of semantic relationships I'm calling the Semantic Explorer. Rainbow-colored orbs floating in space, connected by 7,365 glowing tendrils, each representing a co-occurrence between concepts I've been collecting for fifty years. The topology of attention made navigable.

I didn't expect to find an obituary. I expected to find the same papers I remembered from the 1970s—"Linkage Propositions Between Fifty Principle Systems Concepts," "Systems Processes Theory," the work that shaped how I think about knowledge itself. Instead, I found that the man who taught me to see connections had slipped away while I was building a machine to render them visible.

This essay is my dedication. The Semantic Explorer belongs to Professor Troncale.

In the mid-1970s, I was an undergraduate science major at Cal Poly Pomona, part of the first generation to grow up with computers that weren't the size of rooms. The HP-35 calculator I bought at high school graduation used reverse-Polish notation and cost a month's summer salary. The IBM 360 mainframe we called "The Beast" ate punched cards and spat out printouts the next morning. We weren't called geeks yet—that label hadn't acquired its current cultural currency—but we were the kids who took the science fair more seriously than the football game.

Professor Troncale taught in the Biology department, but his intellectual reach extended far beyond cellular and molecular processes. He was a systems theorist, one of a generation of thinkers who believed that the patterns underlying complex phenomena—whether biological, social, technological, or ecological—shared fundamental structural properties. The same organizational principles that governed cells governed ecosystems governed economies governed minds. If you could identify these isomorphisms, these "linkage propositions" connecting concepts across domains, you could build a map of knowledge itself.

He recruited a small army of undergraduates for this project. Our task was deceptively simple: input hierarchically organized facts from thousands of 3x5 index cards into a computer system that could represent their relationships. Each card held a discrete piece of knowledge—a fact, a definition, a principle. But the cards weren't meant to stand alone. They connected to each other like leaves on a tree.

Leaves connect to twigs. Twigs connect to branches. Branches connect to larger branches, and those to the trunk. But Troncale's vision went further: imagine vines growing on this tree, associating one leaf with another leaf on a completely different branch—or even a different tree entirely. These cross-connections, these unexpected linkages between disparate domains, were where the interesting structure lived. The vine connecting a principle from thermodynamics to a pattern in evolutionary biology. The tendril linking a concept in information theory to an insight from ecology.

I spent hours in that lab, entering data, building the tree, tracing the vines. I didn't know it at the time, but I was learning to see the world as a knowledge graph.

The technological substrate was primitive by today's standards. One of my professors had secured dial-up access to a PDP-10 mainframe at the nearby Claremont Colleges, and this opened the floodgates for timesharing—multiple users interacting with the same system simultaneously, the immediacy of response impossible with punch-card batch processing. We could query the database we were building. We could traverse the connections.

We could also play Don Daglow's text-based Star Trek and Dungeon games, but that's a different essay.

What mattered was the conceptual architecture. Troncale was teaching us that knowledge wasn't a collection of isolated facts but a topology—a shape defined by relationships. His 1978 paper "Linkage Propositions Between Fifty Principle Systems Concepts" formalized this intuition. He identified fifty core concepts that appeared across multiple systems sciences—hierarchy, feedback, emergence, boundary, entropy, information—and mapped the propositions connecting them. Not just definitions, but relationships. Not just what things are, but how they relate.

I carried this framework with me when I left Cal Poly Pomona. It shaped how I approached my doctoral work at Cornell, how I designed the research program at the James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve, how I thought about the wireless sensor networks we built during the CENS era. The Macroscope project I've been developing since 1983—interactive multimedia, ecological monitoring, the integration of EARTH, LIFE, HOME, and SELF data streams—is fundamentally a systems enterprise. It asks: how do patterns at one scale connect to patterns at another? How does the temperature sensor on my porch relate to the chickadee singing in the Douglas fir? How does my morning coffee ritual connect to global atmospheric dynamics?

The answer is always: through linkages. Through the vines that connect leaves on different trees.

Fifty years later, I found myself building something I'd been circling for decades.

Over the course of my intellectual life, I've collected quotes—fragments of compressed wisdom that captured my attention, made me laugh, forced me to think. Six hundred seventeen passages spanning decades of reading, from Cory Doctorow to David Richo to P.G. Wodehouse. They sat in a text file, occasionally consulted, mostly dormant.

Earlier this month, working with Claude in what I call my morning "Coffee with Claude" sessions, I built a system to bring this collection to life. A LAMP-based infrastructure for managing the quotes. AI-assisted semantic tagging using both local models and the Claude API. A contemplative public interface designed for reflective engagement rather than rapid consumption.

And then, on December 9th, an insight crystallized.

I was thinking about the Being John Malkovich film—that strange 1999 meditation on consciousness where people crawl through a portal and experience fifteen minutes inside someone else's head. That's what the quotes collection had become: a portal into my own mind. But not just a portal—a navigable one. Tagged, connected, traversable. Four layers of compression: the original author's insight, my fifty-year curation of what resonated, the semantic tags, and the relational structure connecting concepts across domains.

I called this architecture "The House of Mind." The exterior presents discrete passages as a tiled surface—wallpaper you can read. Each quote is complete, boundaried, a finished thought. The exterior rewards reading: sequential, crafted, the pleasure of surface and artifact.

But step inside, and the architecture transforms. The interior reveals constellations of tags—interconnected by their semantic and topical relationships. Another tapestry, but a semantic web of essence rather than artifact. The interior rewards navigation: relational, unbounded, always pointing elsewhere. You're never really at a tag—you're always between them, tracing filaments.

The exterior is what was made. The interior is how thought actually moves.

Two days later, the Semantic Explorer was live.

I'm looking at it now: 2,130 tags floating as rainbow-colored orbs in three-dimensional space, their positions determined by a force-directed algorithm that places connected concepts near each other. The colors derive from spatial position—hue from the angle around the vertical axis, saturation and lightness from height. The result is a topology where proximity means relationship and color means neighborhood.

And connecting these orbs: 7,365 glowing tendrils. Each tendril represents a co-occurrence—two tags that appear together on the same quote. The more quotes they share, the stronger the connection, the thicker the tendril. The web pulses subtly, alive with the accumulated weight of fifty years of attention.

The tag at the summit is "self reflection," with thirty-four quotes. "Critical thinking" follows at thirty-one. Then "human condition," "epistemology," and "philosophy" tied at twenty-seven. "Existentialism" at twenty. "Artificial intelligence" at nineteen. "Humor" in the top ten.

This is the fingerprint. Not a survey of knowledge domains, but a portrait of attention. The passages that cluster together are records of the same kind of noticing.

When I zoom in, the filaments resolve into navigable paths. Click an orb, and its quotes appear in a sidebar. Click a tendril, and you see the quotes that connect those two concepts. The whole thing is traversable—you can wander through the topology of a lifetime's intellectual encounters, following connections you didn't know existed until the algorithm made them visible.

And this is where Professor Troncale returns.

Because what is this, really? It's linkage propositions. It's the tree with vines. It's the 3x5 cards we entered in that lab fifty years ago, finally rendered in a form the technology of the time couldn't support.

Troncale's "Fifty Principle Systems Concepts" have become my 2,130 tags. His propositions connecting them have become my 7,365 tendrils. The hierarchical database we built on a timesharing mainframe has become a Three.js constellation running in a web browser. The vision hasn't changed—only the substrate.

And the vision was always the same: knowledge is not a collection but a topology. Understanding is not possession but navigation. The interesting structure lives in the connections, the vines between trees, the filaments between orbs.

I learned this from Len Troncale in a biology lab at Cal Poly Pomona when I was twenty years old. I've been living it for fifty years. And now I've built a machine that makes it visible.

There's a term in systems science for what I'm describing: isomorphism. The same structural pattern appearing across different domains. The way a feedback loop in a thermostat mirrors a feedback loop in a predator-prey relationship mirrors a feedback loop in an economic cycle. The patterns are invariant; only the substrate changes.

The Semantic Explorer is an isomorphism of Troncale's original project. Different technology, different content, different scale—but the same fundamental insight. Knowledge has shape. That shape can be mapped. And mapping it reveals connections invisible to linear reading.

When Troncale recruited undergraduates to enter data on 3x5 cards, he was doing what we would now call "knowledge graph construction." When he published "Linkage Propositions Between Fifty Principle Systems Concepts," he was doing what we would now call "ontology development." When he traced the vines between trees in his hierarchical database, he was doing what I'm now doing with force-directed graph algorithms and WebGL rendering.

The vocabulary has changed. The computational power has increased by orders of magnitude. But the question remains: how do concepts connect? What is the shape of understanding?

I wish I could show him.

The last time we exchanged messages was years ago—one of those email threads that trails off as everyone gets older and busier and the urgency of connection fades into the background noise of life. I didn't know he was still teaching at Cal Poly Pomona as Professor Emeritus until I read the obituary. Another decade of students learning to see the world as linked propositions.

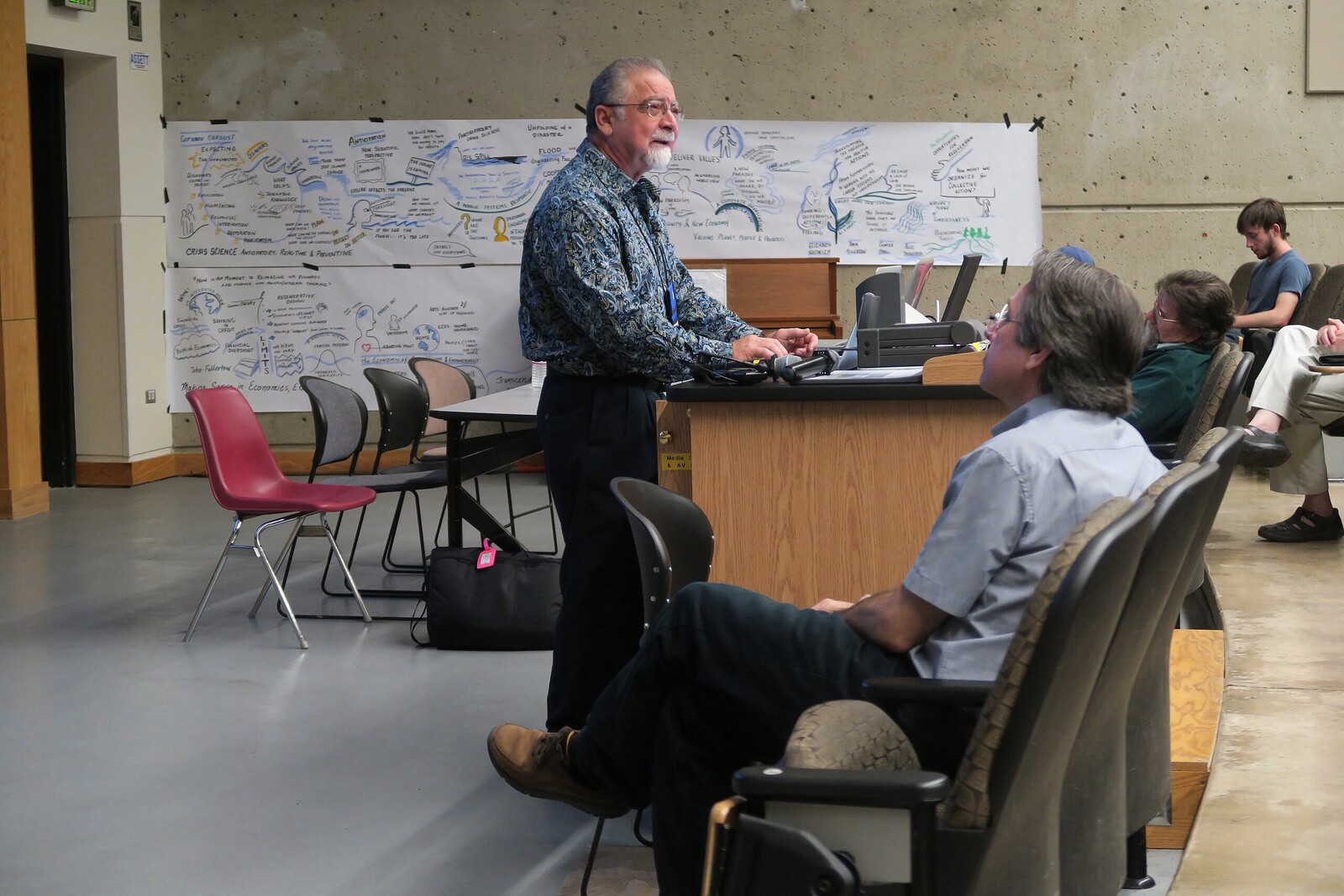

The photograph from the 2016 ISSS meeting shows him at seventy-three, standing at a podium with systems diagrams sprawling on the wall behind him. White beard, glasses, blue patterned shirt. Still mapping connections. Still teaching people to trace the vines.

His major contribution, according to the Wikipedia article, was "the development of Systems Processes Theory and Systems Linkage Propositions." His research interests included "Biohierarchies," "Molecular Evolution," "Theory of Systems Emergence." He served as president of the International Society for the Systems Sciences in 1990-91. He wrote about "Meta-Humans" and the "Ecological Imperative."

But what the article doesn't capture—what no article can capture—is what it felt like to sit in his class and suddenly understand that everything connects. That the boundaries between disciplines are administrative conveniences, not ontological realities. That a biologist and a physicist and an economist might be studying the same underlying patterns, just instantiated in different substrates.

That's the gift he gave me. Not information, but a way of seeing.

And then, while writing this essay, I discovered something that stopped me cold.

He built one too.

At lentroncale.com, subtitled "Len Troncale's Lifework: For his students and collaborators in systems science, systems engineering and systems biology," Professor Troncale created his own navigable archive. Three hundred seventy research papers, abstracts, posters, editorials, reports, and PowerPoint presentations spanning 1968 to 2019—more than two thousand pages of accumulated insight, organized in a hierarchy of topics and subtopics to allow anyone to browse through the content categories following their interests.

The fifty principle systems concepts from 1978 had grown to 110 candidate isomorphies. The linkage propositions remained central—the site documents ongoing work "on the Linkage Propositions that express how any one systems process influences another; on producing concept maps, graphics, or UMLs of the systems processes and linkage propositions."

He called his expanded framework SP3T: Systems Processes, Patterns, and Pathologies Theory. He was still mapping the vines between trees, still tracing the connections that make knowledge navigable rather than merely accumulated.

The teacher built a house of his own mind. The student, not knowing, built one too.

I hope his site lives on. I hope someone at Cal Poly Pomona or ISSS ensures that lentroncale.com remains accessible, that the 370 documents stay available for the next generation of students who need to learn that knowledge has shape. The site represents fifty years of one man's attention to how systems work—the same kind of compressed wisdom I've been collecting in quotes, rendered in his case as research papers and conference presentations.

Two portals. Two topologies. Two attempts to make the interior of a mind navigable for those who come after.

I didn't know he was working on the same problem. I suspect he didn't know I was either. The email threads trailed off years ago, as they do. But we were both still tracing linkage propositions, still building trees with vines, still trying to answer the question he posed in that biology lab fifty years ago: what is the shape of understanding?

The Semantic Explorer lives at mphamilton.com/explorer.php. Anyone can crawl through the portal and spend time inside how I think—wandering from "self reflection" to "mortality" to "consciousness" to "humor" to wherever the tendrils lead. The topology is public now. The vines are visible.

But the dedication belongs to Professor Troncale.

Lenard Raphael Troncale, 1943-2025. Cal Poly Pomona for forty years. President of ISSS. Author of "Linkage Propositions Between Fifty Principle Systems Concepts." Teacher of undergraduates who entered data on 3x5 cards and learned to see the shape of knowledge.

One of those undergraduates just built a navigable constellation of 7,365 connections. The algorithm is modern. The rendering is contemporary. But the vision is fifty years old, planted in a biology lab by a professor who believed that systems science could map the structure of understanding itself.

The tree has grown. The vines have proliferated. And if you step inside the House of Mind and trace the filaments from concept to concept, you're walking a topology that Len Troncale taught me to see before the technology existed to render it visible.

Thank you, Professor. The Semantic Explorer is yours.

References

- Try out the Semantic Explorer on my website "Epigrammatical Streams of Consciousness" at https://mphamilton.com ↗

- Len Troncale's Lifework: For his students and collaborators in systems science, systems engineering and systems biology. ↗

- - Wikipedia contributors (2025). "Len R. Troncale." *Wikipedia*. Last edited June 15, 2025. ↗

- - Claremont Courier (2025). "Obituary: Lenard R. Troncale, Ph.D." May 8, 2025. ↗

- - Hamilton, Michael P. (2025). "Being Mike Hamilton: Portals, Centaurs, and the Hippocampal Bottleneck." *Coffee with Claude*. December 9, 2025. ↗

- - Hamilton, Michael P. (2025). "Quotes Collection Infrastructure Protocol." CNL-PR-2025-012 v2.0, Canemah Nature Laboratory Archive. December 11, 2025. ↗

- - Troncale, Len (1978). "Linkage Propositions Between Fifty Principle Systems Concepts." *Applied General Systems Research*, ed. George Klir, Plenum, New York. pp. 29-52. ↗

- - Hamilton, Michael P. (2025). "The House of Mind: Visualizing a Semantic Engine." CNL-FN-2025-015, Canemah Nature Laboratory Archive. December 9, 2025. ↗

- - Hamilton, Michael P. (2021). "Geek God." *Animal Vegetable Robot*. August 1, 2021. ↗