Making the Invisible Visible: From Edge Detection to the Tricorder

This morning I read a paper in Nature Communications that stopped me mid-coffee. Researchers in China have demonstrated something called the Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager—MASI—achieving 780-nanometer resolution through computational phase synchronization across distributed sensor arrays. They can resolve features smaller than a red blood cell using cheap sensors computationally fused into a single virtual aperture.

The tricorder, I thought. They're building the tricorder at last.

I've been waiting for this paper for forty years—or something like it, some breakthrough that finally closes the gap between what we can see and what we can measure in field ecology.

The dream predates the technology. In 1984, I wrote a proposal for something called the Electronic Museum Institute, describing a portable "Field Logger" that would record "stereoscopic color video" and "distance measurements between objects" while an ecologist walked through a forest. The vision was clear: a handheld device that could capture not just images but geometry, not just moments but measurable structure. The hardware didn't exist. Neither did the algorithms. But the question was already formed: how do we make ecosystems legible through computational sensing?

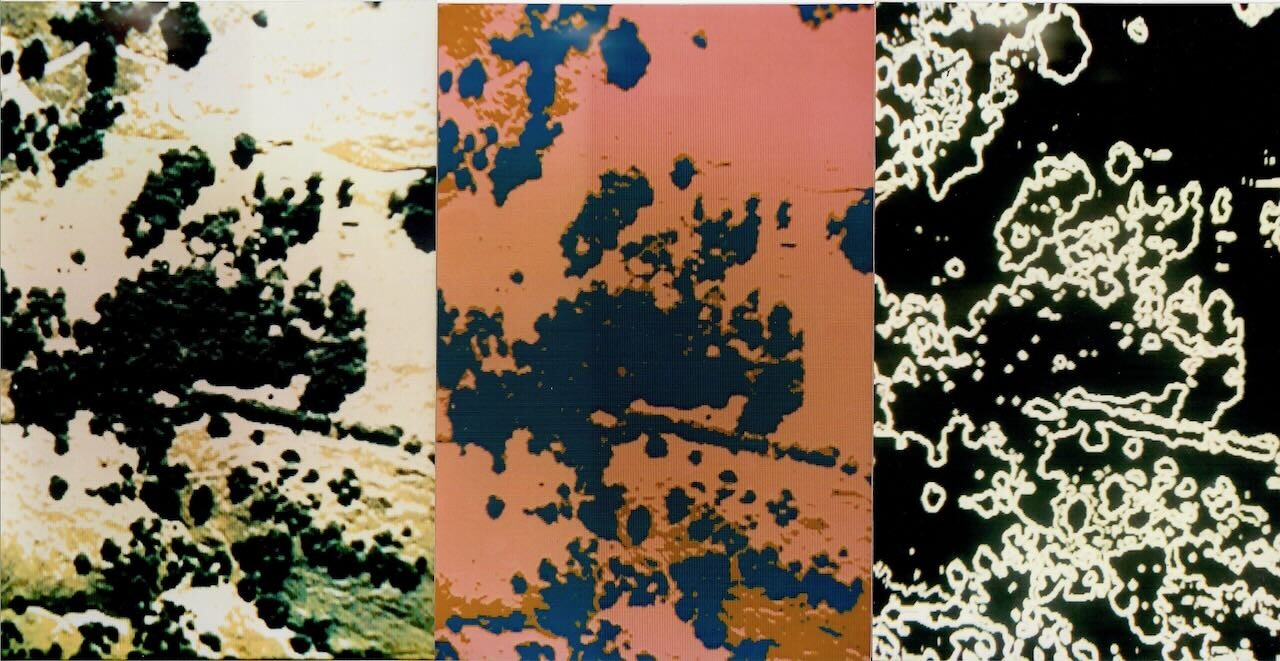

Nine years later, I got my first glimpse of what computation could extract from images. Edge detection. Sobel filters. Convolution kernels finding crown boundaries in scanned aerial photographs. I was running image processing on an IBM PC-AT, funded by Ted Hullar at UC Riverside who had read that 1984 proposal. Crown perimeters appeared as crisp white arcs on a black screen. Gap edges traced fractal boundaries where tree met sky. The geometry of canopy structure—something I had described qualitatively for a decade—became quantifiable.

The computer found structure the eye couldn't extract. But this was analysis after the fact, applied to photographs taken from aircraft. The tricorder remained distant—a device you would carry through the forest, capturing geometry in real time.

That same year, I carried three dosimeters on my body in western Russia.

The Chernobyl project started in 1992 when David Hulse at the University of Oregon invited me to join an international collaboration using GIS to model radionuclide transport through agricultural landscapes in the fallout zone. The proposal we submitted to Apple Computer listed hardware requirements including "the Walkabout Datalogger"—Powerbooks configured for field data collection. That name appeared in a formal proposal three years before the first Palm Pilot existed. The concept from my 1984 Field Logger had crystallized into something with a name, something we intended to build.

What I remember most from the trip is surrealism: dosimeters tracking my accumulating exposure while I documented field sites alongside Russian scientists who had already absorbed dangerous doses collecting the soil samples that made our modeling possible. Cesium-137 and Strontium-90 move through ecosystems along predictable pathways—atmospheric deposition to soil, soil to plants, plants to animals, animals to humans. The half-life of Cesium-137 is thirty years; the contaminated landscape would remain hazardous for generations.

By modeling radionuclide uptake through food webs, we could predict which villages faced highest exposure, which crops posed greatest risk, which interventions might reduce cumulative dose. The invisible poison became visible through data visualization and clear explanation.

Here was the same architecture I had applied to crown boundaries—sensing, processing, disseminating knowledge about complex systems—applied to invisible contamination. The computer tracked poisons the body couldn't sense. But the sensing itself remained indirect: soil samples collected by hand, analyzed in laboratories, interpolated across landscapes. The tricorder would measure directly, instantly, in the field. We weren't there yet.

The technologies have transformed beyond recognition since 1993. The Powerbook I carried in Russia had a 25 MHz processor; the iPhone in my pocket has roughly a million times more computational power. But the transformation that matters most for field work happened in the camera.

Computational photography emerged gradually, then suddenly. iPhone HDR combined multiple exposures. Panorama modes stitched sequential frames. Portrait mode used machine learning to separate foreground from background. Each advance represented the same principle: computation compensating for sensor limitations. You can't fit a large aperture in a thin phone, but you can fuse exposures. You can't measure depth with a single camera, but you can infer it from learned features or stereo pairs.

The iPad Pro added LiDAR in 2020—time-of-flight depth sensing capturing millimeter-level geometry within five meters. Stereo cameras extend 3D capture to thirty meters with centimeter resolution. Spherical cameras capture complete environmental context. The walkabout datalogger I imagined in 1984 was arriving as a mass-market product.

But there remained a gap. All these sensing modalities work through geometric inference—measuring time-of-flight, matching stereo features, reconstructing structure from motion. None directly measures surface geometry with precision enough to track subtle change over time: millimeter-scale lichen growth, micron-scale leaf deformation under drought, the slow fissuring of bark as trees age. The tricorder would capture metrological precision—measurement exact enough to detect change at biological scales. Current tools approached but didn't arrive.

The MASI paper describes something fundamentally different. Where conventional cameras measure only light intensity, MASI captures the complete optical wavefield—including phase information that directly encodes surface geometry. When coherent light reflects from a surface, the phase of the returning wave carries precise information about distance traveled. That distance is geometry. Phase is direct measurement of surface shape.

The challenge has always been synchronization. To combine measurements from multiple sensors, you need sub-wavelength precision—nanometers for visible light. Traditional approaches require mechanical stability that limits practical deployment. What Chen and colleagues demonstrated is computational phase synchronization: algorithms that align wavefields from distributed sensors by optimizing for maximum energy concentration in the reconstructed image. No mechanical calibration required. The math finds alignment.

The result: 780-nanometer lateral resolution, 6.5-micrometer axial resolution, at working distances of two centimeters. Features smaller than a red blood cell, resolved without lenses, using cheap sensors fused computationally into a synthetic aperture larger than any individual component.

What would such sensing mean for field ecology?

Every ecologist knows this frustration: you find something remarkable—a lichen colony, a nest cavity, an erosion pattern—and when you return months later to measure change, you can never find exactly the same spot. GPS gives meters of uncertainty. Visual landmarks shift with seasons. Fiducial markers require installation and maintenance.

But if you capture precise 3D geometry—the unique topography of a bark patch, the configuration of branches against sky—the scene itself becomes the registration target. You don't need identical position, just enough geometric overlap for computational alignment. The data tells you where you are relative to previous observations. The landscape remembers where you stood.

This is what I was reaching toward in 1984 when I described the Field Logger recording stereoscopic video and distance measurements. The intuition was right. The technology wasn't there. Forty years later, MASI suggests it may finally be arriving.

The catch is coherent illumination—MASI requires laser light. You can't point it at a sunlit forest and expect it to work. But the principle of computational aperture synthesis is more general than the specific implementation. The physics works. The engineering advances.

I have been building toward this question for my entire career. Edge detection in 1993, finding crown boundaries the eye missed. Dose models in Russia, tracking invisible poison through food webs. Embedded sensor networks at CENS, watching forests in real time. iPad LiDAR at Canemah, capturing geometry with consumer hardware. Each approach moved closer to the tricorder. Each fell short in specific ways.

This is what computation does for observation: it finds structure the eye cannot extract, tracks poisons the body cannot sense, measures geometry light alone cannot reveal. The MASI breakthrough suggests metrological 3D capture may become practical for field ecology—not tomorrow, not with current hardware, but perhaps within years.

Whether I live to use such a device in the field is uncertain. What is certain is that the question persists—that the arc from convolution kernels to coherent wavefields continues, that someone will eventually carry a true 3D scanner into the forest and see what has never been measured before.

In 1993, I watched white lines trace crown boundaries on a black screen. The computer found structure. Thirty-two years later, researchers find phase. The invisible becomes visible. The unmeasurable becomes quantified.

The walkabout continues.

References

- - Wang, R., Zhao, Q., et al. (2025). "Multiscale aperture synthesis imager." *Nature Communications* 16:10582. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65661-8 ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. (2025). "Electronic Museum Institute: A Historical Reference Document." Canemah Nature Laboratory Technical Note CNL-TN-2025-003. https://canemah.org/archive/CNL-TN-2025-003 ↗