The Serialization Engine: From Campfire to Cognitive Prosthesis

The campfire had burned down to coals by the time I reached the creation story.

It was the mid-1970s. I was a wilderness park aide on Mount San Jacinto, standing before a semicircle of campers in the stone amphitheater at Idyllwild. The evening program was mine to shape. I had learned that the way to hold an audience under the stars was not to lecture about ecology or recite fire safety regulations but to tell stories—and the most powerful stories I knew were not my own.

The Cahuilla people had lived in the shadow of that mountain for more than three thousand years before Europeans arrived. I knew this because I had met two of their elders.

As a nineteen-year-old student at Cal Poly Pomona, I was taking a class called "The Native American in Literature." One assignment required us to explore a particular group of native people and their contributions. I had just begun weekend commutes from Pomona to my state park job at 8,500 feet on the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway. The route passed through Banning and the exit for the Morongo Reservation and the Malki Museum. I thought: maybe I should learn about these people.

At the museum I met Katherine Siva Saubel and Jane Penn, the founders—and, as it turned out, cultural authorities with particular expertise in the ethnobotany of their people. Katherine had learned traditional plant knowledge from her mother, a Cahuilla medicine woman, and had recently co-authored with anthropologist Lowell Bean the book Temalpakh—"From the Earth"—covering more than 250 plants and their uses, now considered the authoritative work on Cahuilla ethnobotany. In my naive nineteen-year-old ignorance I asked whether the Cahuilla had used the high elevations of San Jacinto State Park.

Their answer changed my understanding of what knowledge could be.

Every rock had been looked under, they told me. Every plant and animal was known.

Three thousand years of systematic observation, encoded in cultural memory and practice. A complete documentation system for the territory, maintained across generations without writing. The mountain I was learning to interpret as a park aide had already been fully interpreted—by people whose descendants still lived in its shadow.

When I revealed my own interests in field botany—I was taking a plant identification class—Katherine and Jane asked if I had seen Asclepias, milkweed, in the high country. I thought so. And so began a relationship between me and these learned women to explore the ethnobotany of the upper elevations. The museum had an ethnobotanical garden—the Temalpakh Garden, a living illustration of Katherine's book—but wanted to expand the collection to include high-elevation species. I became a seed collector for them, carrying Cahuilla ethnobotanical knowledge up and down the mountain in the form of seeds and specimens.

The irony I would not understand for years: Katherine Saubel was a close friend of Harry James, who still lived at the James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve until his passing in 1978. Harry had founded conservation organizations like the Desert Protective Council and lobbied for native peoples' rights. Katherine and Jane would hold board meetings for the Malki Museum at the reserve—the same reserve where I would later spend twenty-six years as director. The chains of transmission were already linking, though I could not see them yet.

Their creation story begins in primordial darkness, where twin balls of lightning—manifestations of Amnaa, Power, and Tukmiut, Night—gave birth to the creator brothers Mukat and Temayawut. Mukat shaped the people from his own heart; Menily, the Moon Maiden, taught them the arts of civilization—games, dancing, weaving, marriage. When Mukat died, turmoil erupted. The people dispersed, following the birds who seemed to know where something better might be found. They wandered far, some say as far as South America, lost in snowstorms, dying along the way, until finally they found their path home to the Coachella Valley.

That journey home is encoded in the Bird Songs—more than three hundred pieces sung in precise order across three nights, from dusk to dawn. The singing begins at nightfall, symbolizing the start of the migration, and ends at sunrise, symbolic of the return home. Over the years I heard these songs in person at the Malki Museum's annual Kéwet fiesta, held each Memorial Day weekend since 1966—bird singers performing in the ramadas, the smell of pit-roasted beef and fry bread, the chain of transmission alive and continuing. They had been sung around fires on that mountain since time immemorial.

I understood, standing at the campfire amphitheater with pine smoke in my clothes and starlight above the ridge, that I was doing something very old. Not performing—participating. Extending a chain of transmission that preceded writing, preceded agriculture, preceded everything we call civilization. The campers leaning forward in the firelight were not my audience; they were the next links in a chain that would continue after all of us were gone.

I did not know then that I would spend my career on that mountain, that I would become director of a biological reserve on its slopes—the same reserve where Katherine held her museum board meetings—that I would write proposals for electronic systems to document the ecological knowledge accumulating there. I did not know that forty-nine years later I would be drafting this essay with an AI collaborator, announcing a science fiction novel built through methods I could not have imagined in 1976.

But I knew something that night that I have not forgotten: stories are not optional equipment for human beings. They are the means by which we transmit what matters across time. They shape what we become by shaping what we tell.

The trajectory from campfire to cognitive prosthesis is not a break but a continuum.

I have been thinking about this continuum for months now, since I began documenting the methodology behind my collaboration with Claude on a science fiction novel called Hot Water. The first technical note, "The Novelization Engine," described the infrastructure we built: living story bibles, character templates with voice anchors, reader state tracking, an eleven-component scene schema. The document framed this as a method for completing long-incubated fiction through AI collaboration.

But working through the implications over these past weeks—most recently during three days in a cabin near Mount Baker—I have come to understand that the methodology produces something more fundamental than a novel. It produces a story system: a documented architecture capable of rendering into multiple formats while preserving narrative integrity.

The novel is one instantiation. A screenplay adaptation would be another. A graphic novel, an audio drama, a young adult version pitched to a different register—all possible without loss of the story's spine. The documentation infrastructure that dialogic production requires turns out to be format-agnostic. What I thought was a method for writing novels is actually a method for building transferable narrative architectures.

I have called this generalized framework the Serialization Engine, adopting both meanings of the term. In computer science, serialization converts complex objects into formats that can be stored, transmitted, and reconstructed elsewhere. In publishing, serialization releases content episodically. Both senses apply: the methodology serializes stories into transferable components, and those components support serial release across platforms.

The technical note documenting this framework is now archived at the Canemah Nature Laboratory. But the deeper finding is not technical. It is about the continuity between that campfire in 1976 and this morning's writing session.

I returned from Mount Baker to find a newsletter from the Santa Fe Institute announcing a working group convened December 10-12: "Towards a Data-Driven Science of Stories."

The timing felt almost scripted.

Computer scientists, folklorists, physicists, cognitive neuroscientists, and mathematicians gathered to connect approaches to understanding narrative. Peter Dodds, a systems scientist at the University of Vermont, framed the ambition: "We want to illuminate the spectrum of stories across time and cultures, just like other fields have found spectrums of stars, species, or words."

The working group aims to develop methods for mapping story plots, creating visual representations of character networks over time, and building rich datasets that researchers can use to identify fundamental story features. Sam Zhang, a statistician and co-organizer, articulated the constraint: they want "a science of stories that honors what a story is, and doesn't reduce it to a bag of words."

This is the analytical approach—taking existing stories as data, decomposing them into measurable structures, identifying patterns across thousands of narratives. The Serialization Engine represents the complementary generative approach—building stories as parameterizable systems, documenting architecture explicitly, enabling transformation across formats.

The convergence suggests something real is being mapped. When independent research programs arrive at similar structures from opposite directions, the structures are probably not artifacts of method. They are probably features of the territory.

And yet both approaches—the SFI working group's analysis, my Serialization Engine synthesis—are technological overlays on something that precedes all technology. Dodds defines stories as conveying "knowledge about how to navigate the world," involving "characters and events that are connected and unfold over time, wrapped around essences of power, danger, and survival."

That definition applies equally to Beowulf, to Pride and Prejudice, to the sitcom Friends—and to the Cahuilla creation stories I told on Mount San Jacinto fifty years ago. The Bird Songs that mark the passage of night toward dawn encode knowledge about navigation, connection, power, survival. They have done so since time immemorial. The phrase is not metaphor; it is phenomenological claim. There was never a time when we were not doing this.

The novel I have been building is called Hot Water.

The premise: the Chicxulub asteroid that ended the age of dinosaurs sixty-six million years ago carried crystalline substrate from an alien world—material whose quantum chemistry records evolutionary history at a molecular level. The Pictish symbol stones of early medieval Scotland turn out to be rudimentary navigation interfaces for reading aspects of this archive. A team of scientists discovers that Earth has been documented since the impact.

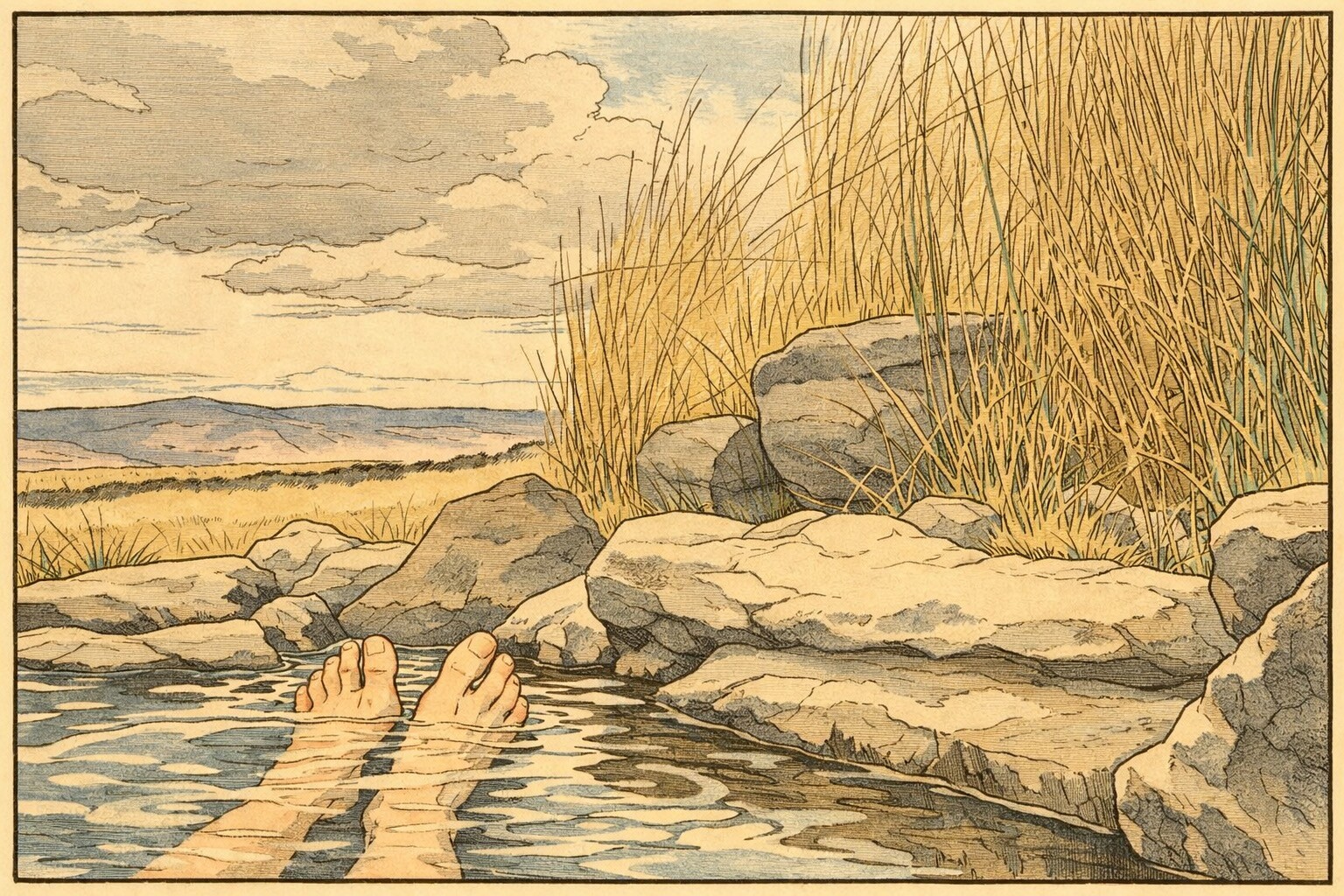

The story incubated for a few decades, usually when I'm soaking at a hot spring. For a decade I played in the SCA, a medieval reenactment society where you choose a persona from the pre-17th century world, do your own research, and immerse yourself in a creative form of time travel on weekends. Between my day job as an ecologist, my newfound fascination in medieval Scottish standing stones, the stress reduction benefits of hot mineral waters, the ideas for a novel slowly percolated. Scattered notes were made and the time had arrived to dust them off and apply my new cognitive prosthesis. Working with Claude, I found that the methodology excavated material I had been carrying for decades. The AI did not generate the ideas; it helped me recover what was already present.

Hot Water is a story about an archive that records observers, that notices when it is finally being read. I wrote it using a methodology that documents its own architecture.

Every rock had been looked under. Every plant and animal was known.

That was the Cahuilla documentation system—three thousand years of observation encoded in songs and ceremonies and the 250 plants catalogued in Temalpakh, knowledge that passed from a medicine woman to her daughter and from that daughter to a seed-collecting nineteen-year-old at a small museum in Banning.

The Bird Songs begin at dusk and end at dawn because the structure carries meaning. The night passage is the migration itself—the long wandering, the following of birds, the snowstorms and losses. The dawn is the homecoming. Form carries content.

The Serialization Engine aims at the same integration: stories that entertain and transmit knowledge about navigating the world. The campfire has not gone out. It has expanded to circles the original tellers could not have imagined, carried by technologies that would have seemed magical.

Hot Water is available at:

Welcome to the circle.

The technical notes documenting the Novelization Engine and Serialization Engine methodologies are archived at canemah.org.

References

- Hot Water Volume One: Signal ↗

- - Clark, A. & Chalmers, D. (1998). "The Extended Mind." Analysis, 58(1), 7-19. ↗

- - Saubel, Katherine Siva & Bean, Lowell John (1972). *Temalpakh: Cahuilla Indian Knowledge and Usage of Plants*. Malki Museum Press. ↗

- - Malki Museum (2025). "Kéwet." MalkiMuseum.org. https://malkimuseum.org/pages/kewet ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. (2025). "The Cognitive Prosthesis: Writing, Thinking, and the Observer Inside the Observation." Coffee with Claude. https://coffeewithclaude.com ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. (2025). "The Novelization Engine: A Methodology for AI-Augmented Long-Form Fiction Development." Canemah Nature Laboratory Technical Note CNL-TN-2025-022. https://canemah.org/archive/document.php?id=CNL-TN-2025-022 ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. (2025). "The Serialization Engine: A Generalized Framework for Format-Agnostic Story System Development." Canemah Nature Laboratory Technical Note CNL-TN-2025-023. https://canemah.org/archive/document.php?id=CNL-TN-2025-023 ↗

- - Santa Fe Institute (2025). "Constructing a science of stories." SFI News. https://www.santafe.edu/news-center/news/constructing-a-science-of-stories ↗